September 23, 2024

We Can’t Shield Our Kids From Failure. And We Shouldn’t.

“Helicopter” parents (monitoring every detail of their children’s lives) and “snowplow” parents (ensuring no obstacles get in their children’s way) mean well: They genuinely believe that shielding their children from failure can help them succeed.

But the more I read about raising successful, resilient kids, the more I have come to understand that these parenting approaches don’t work. In fact, psychologists say that “snowplow” parents may unwittingly produce “snowflakes,” children who lack resilience in the face of difficulties. Instead, allowing children to experience setbacks and work through them is a much more effective approach for ensuring their future success.

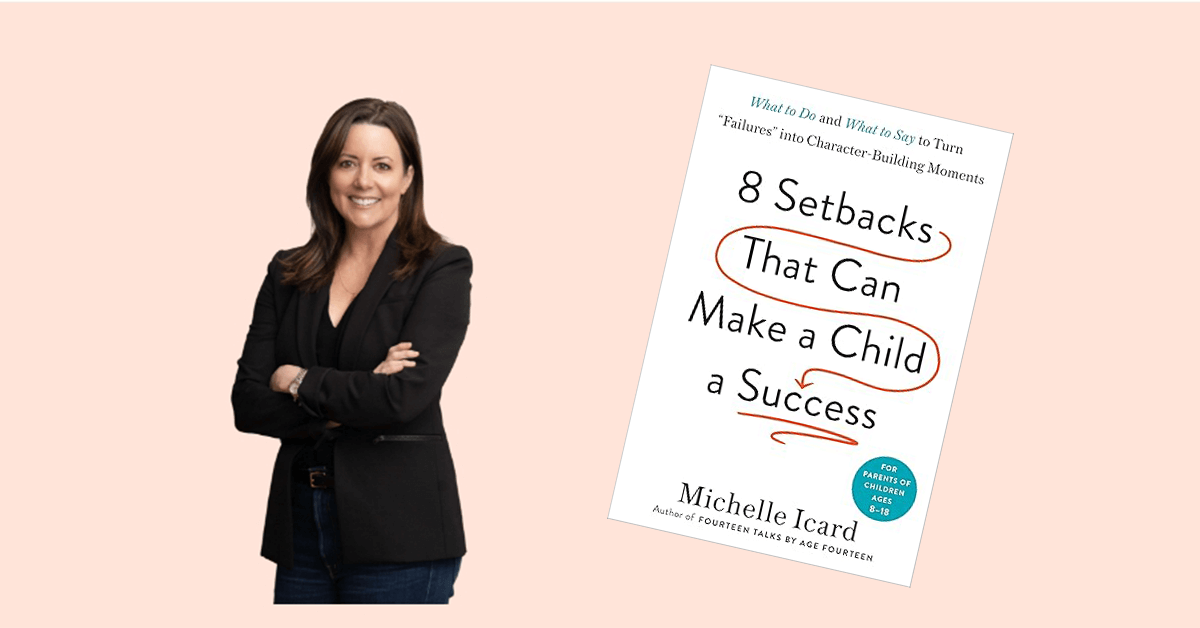

In her latest book, 8 Setbacks That Can Make a Child a Success, acclaimed parenting expert Michelle Icard demonstrates that children are safer and more successful when they are allowed to take risks and work through failure. Icard contends that “not being perfect is so key to their future success.” If kids fail to launch, Icard suggests, it’s because they’ve never been given genuine opportunities to be independent. Icard believes that when kids are given time to sit with their mistakes and gain practice addressing them,…