September 19, 2023

It was 2004 when a teacher of color was sent by the girls’ school at which he taught to Hawaii for the People of Color Conference (POCC). Coincidently, it was also the start of a movement at independent schools to challenge the Western canon, an exciting pivot away from the Western survey course that this teacher had inherited. He had been accepted into College in the UK on the strength of his academic skills in History but was never exposed to a book like Europe and the People without History, which changed his outlook after he came to the United States. When he was a middle school student at one of the oldest and most iconic independent schools in the world, Harrow School, the school of Winston Churchill and Lord Byron, this teacher had endured racism as a South Asian, not from his teachers but from his fellow students. In his mind, then, as he flew to Hawaii, were the racial slurs an older boy hurled at him daily, deeply hurtful at 13 years old, and leading to tears and support from his older brother. He had developed his tools of retaliation. He simply outperformed all his classmates in virtually every subject, and he relied on his unfailing optimism. He expected to be challenged and to challenge at this conference.

That teacher was me.

On the second day, the attendees were sorted into smaller groups until they found their place in what were called, somewhat innocuously, affinity groups. I dutifully joined the affinity group in which I was placed. We all sat in a circle like a campfire and that felt safe. The moderator started by asking us to “breathe in the moment”. I looked around, seeing nothing odd. She then said,

“I hope as you look at each other, you feel more safe than you have at your school… in life, where you don’t get to be with others of such affinity. Your people. Take a moment to reflect and then let’s go around to have each of you let the group know how you feel.”

One by one the group members started talking about how they felt. And then I realized, I was meant to identify emotionally and intellectually with the individuals in the group simply because they looked (a little?) like me. I am Sri Lankan by birth, and I glide easily into groups both white and of color: with no permanent home after my father’s death at age 9 and with little financial support for our family, I stayed with “foster” families in Ireland, UK, and Germany where people of color were rare in the 70s. When affordable, I returned to Sri Lanka to see my mother, sometimes waiting as much as 2 years. Returning to the affinity group assignment, it felt like an odd demand to identify racially. The more I thought about it as my turn approached, I realized what was being asked of me was the opposite of what I had been taught, in terms of how to think and feel.

It felt tribal.

But I was not sure which tribe I was meant to be part of. I felt at odds with my processes of critical thinking. It felt like, first and foremost, this assignment was leading me to adopt a victim mentality that should direct my thinking. I wondered whether my childhood or the lack of it in a traditional sense, as well as the struggles as a child of color, had left me with a lack of empathy for others’ struggles. Did my pain not enable affinity with the struggles of others, particularly of my race? Was I experiencing the opposite feeling?

Then there was this little problem: I was assigned the Asian affinity group because there was no South Asian affinity group. So none of the group participants looked like me at all: more Chinese or Filipino or people originating from the many countries in the vicinity of the South China Sea. It was my turn to “breathe my safety” into the group. Digging into my most authentic self, one you may recognize in my other writing, I responded to the prompt:

“To be honest, I have never been more afraid in my whole life. Am I meant to look like all of you? Because I don’t look anything remotely like you. More importantly, does safety come first from skin color, and do all our experiences not matter? Surely our experiences transcend our race? Mine do.”

What happened next was even more remarkable. No one responded. No apparent lesson plan at all. The moderator thanked me and moved on!

So let’s take a look at the thinking behind affinity groups. They parse by race because they believe that all races are essentially marginalized in largely similar ways and mostly by whiteness. Kelsey Blackwell, an affinity advocate quoted by POCC attendees, provides a cogent summary in this article: “These [affinity] spaces are crucial to the resistance of oppression”, so that “there can be healing”…“In integrated spaces, patterns of white dominance are inevitable…even when white people are doing the work of examining their privilege”… “The values of whiteness are in the water in which we all swim”…. “Discrimination is like plaque that covered your being at birth”… “It may be argued that to build an inclusive community, caucusing is necessary” citing intersectionality as a means to “strengthen broader movements”… and “Doing race work in an integrated setting is harmful”. She closes by citing a friend: “We don’t need allies (i.e., friends); we need accomplices (i.e., partners in crime).” And the response: “I couldn’t agree more. The act of supporting people of color is one of subversion.” These are all quotes from that article.

Since I last participated at the POCC, the attendance of white people at the conference “has grown exponentially” according to this regular attendee at POCC, to whom I posed the question of whether white people should be allowed to attend the conference. Below is her answer:

“Your question gets right to the heart of the matter: is POCC an affinity space for POC, or a conference about POC… or both? While white people are ‘allowed’ at POCC (according to NAIS, the conference is ‘for people of color and allies of all backgrounds in independent schools’), you asked whether white people should be allowed. And that is very much a live question among NAIS members and conference attendees. For some, the conference is/should be an affinity space for POC (regardless of the NAIS official stance), while others decline to participate in the formal affinity groups that convene at the conference. I appreciate that you’re asking a question about a conference that is almost 40 years old, that has seen the attendance of white educators grow exponentially from its founding into the 21st century, and that continues to challenge itself and be challenged in what it means to ‘be by and for people of color and inclusive of all (2001).'”

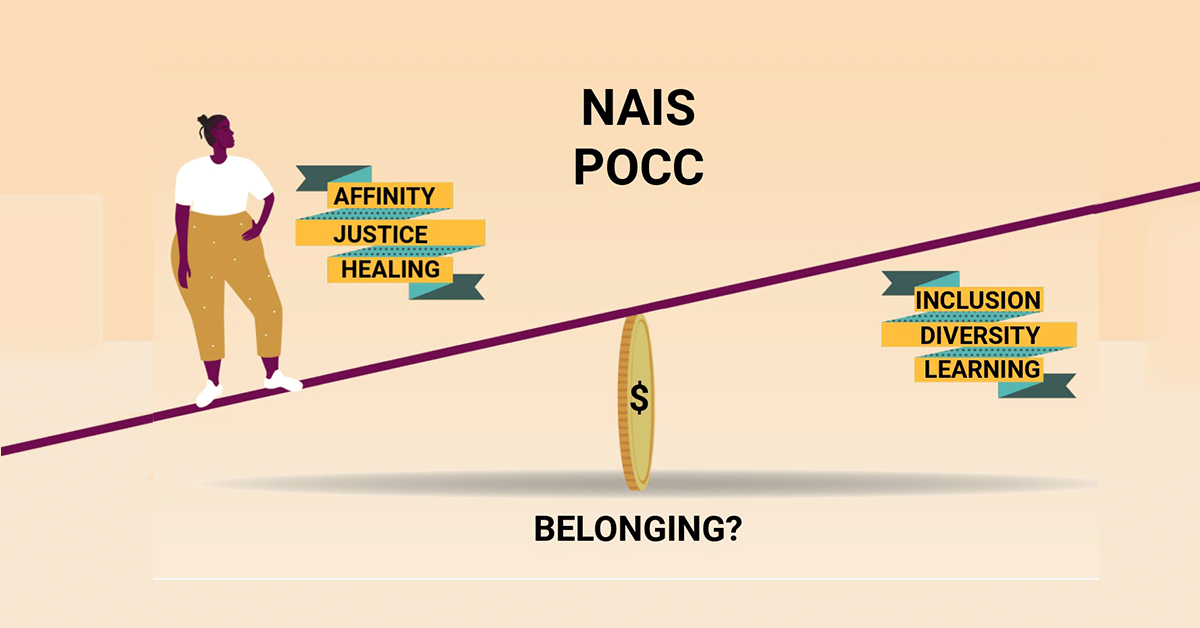

One would have thought that, after 40 years, this simple question would have been settled. NAIS claims that “belonging refers to the emotional and experiential outcome of inclusion” but it has not addressed how that belonging dances with exclusion by affinity. Arguably, independent schools that rely on exclusivity for their market purpose would seem aligned with exclusionary affinity groupings, even though they are now the subject of legal challenges after the recent Supreme Court decisions, and even though they frame their institutions by implication as fundamentally racist. But if more and more white people are being allowed into a conference whose name is directly affinity-associated (and whiteness exclusionary), what exactly is NAIS’s stance on inclusion? Is belonging in some settings an outcome that can be suspended or sacrificed for the advancement of a broader movement combatting the marginalization and oppression of a racial group? The same could be asked of the other broader movements fighting for equality, like women: Should transgender women (assigned male at birth) be excluded from women’s affinity groups because they carry with them the “plaque-like discrimination [of masculinity] they are covered in at birth”?

The National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS), through its forty-year tenure with POCC, has introduced ideologies into our schools. They now bear the burden of clarifying the core beliefs around these ideologies, even if it means that the complexion and demography of the program might change considerably (by excluding white attendees at the People of Color Conference). More recently the conference has become a venue for “like-minded people,” to use the marketing language of NAIS. Such positioning not only negates the whole ethos of affinity-based groupings that posit that white people cannot relate to the marginalization of the oppressed and often corrupt their safety, but it also begs the question of whether the conference is seeking growth in any way and therefore whether it is to be a learning experience at all. To be fair, the meals and entertainment at POCC are always outstanding. It also runs directly counter to the whole purpose of diversity, to embrace the thinking of others (however disparate and divergent, and enabled by diverse experiences). Which is it? Do diversity and belonging need to sacrifice inclusion? Should our class discussions and assemblies be for the like-minded? Or is inclusion an outcome of belonging, as stated on the NAIS website?

What would OESIS do in the same circumstances? That is a big question, but in a sentence, this would be our approach. We would transform affinity groups to “empathy or capacity” groups, we would re-align the input away from racial intelligence to emotional intelligence, and we would make it clear that the important output is not to be heard, but to develop the capacity to listen and thereby think critically. Fundamentally, this has been our non-sectarian and independent approach to inclusion and belonging with schools through professional development (see Head of School Reference). It may offer less opportunity for external redemption through programmatic exhibitionism but it does not rend the fabric of the community in the process of growth.

Ideologies exist at the intersection of faith and power. They are often political, and they lean towards a particular narrative of essentialism. That is why they are dangerous in schools that offer a liberal education. The activists who saw independent schools as a fertile ground to exploit because of their constituents’ privilege and guilt are now seeing the cracks that have formed in their chosen partner, NAIS. The same applies to the DEI practitioners who are now in the throes of frustration at schools. And schools are left to pick up the pieces of fractured communities and teachers who have been disempowered by polarization. It’s time for education to re-emerge and for schools to better manage ideologies (Oppenheimer: How Schools Need to Manage Dogma and Ideology).

You may be interested in reading more articles written by Sanje Ratnavale for Intrepid Ed News.

Unfortunately, Sanje entered the conference and (admittedly) doesn’t know much about the history of PoCC or DEI , generally and… rather than attempt to understand, he labels and reduces the conference to fit into this straw man argument of an article.

Would be nice to encounter more meaningful engagement of ideas, rather than seeing the bogeyman of “essentialism” thrown around.

Well interesting point Chris but is this not racist to have a conference for people of a certain race or skin color as here it is termed. Also is not ‘white’ a color although I’ve yet to see a person the color of snow walking around town.