When I first got married 32 years ago, my wife would complain that I read the most boring books, even for a merchant banker. I had to explain to her that it came from recent trauma. My fixation with central banking, inflation targeting, and currency reserves had come out of September 1992 when George Soros broke the Bank of England, and overnight, my variable interest rate mortgage on my 3-bedroom flat in London went from 5% to 12%. Since then, my fixation has led to a library full of every book on central banking, currency reserve management, inflation theories, and more because, in my mind, there is no more complex system on the planet, except, of course, the human body. It caught my eye, though, recently, that one member of George Soros’s team that shorted the pound had become the Treasury Secretary of the United States under President Trump: Scott Bessent.

Whether you are a school, a teacher or a parent, understanding this moment is important. In this article, I am going to try to explain in as simple a way as possible (not easy) what is happening right now and why much of the media’s analysis misses the mark. It misses the mark because it often fails to layer a finance lens onto the economic picture.

Let me first tell you my conclusions so that you can have them handy as I take you through the analysis and history. First, this is a currency war not a trade war per se- so it is about the dollar. Secondly, there is very much a plan here that resembles previous plans through the 20th century (in 1944 with Roosevelt, 1971 with Nixon and 1985 with Reagan), not some wild, egocentric maniac on the loose. Third, this is not a plan for the US to retreat from the world and be isolated. Fourth, it is very achievable, and the fact that 75 nations are at the negotiating table means it has started well. Finally, it is unlikely to cause much inflation or lead to a US default on its debt, which is literally impossible, as I will explain. My primary source for the analysis of the Trump administration plans is a paper written by the Chairman of Trump’s Economic Council of Economic Advisors, Stephen Miran, just after the election in November 2024 called “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” (See resources below but warning its very technical). Dr. Miran is a former Treasury executive.

Let’s start with the question du jour: Who actually pays the cost of tariffs? Democrats seem incredulous that Trump does not understand that it is the consumer who does because there is typically a pass-through by the importer. After all, a surcharge is levied at Customs, and the exporter is responsible for it, right? No. We have to look deeper.

Here is what typically happens so long as the tariffs do not destroy all profitability for the exporter. The exporting country devalues its currency just as China did in 2018-2020 with the first round of tariffs, and is doing so again. That means the $100 of products spent by the US importer buys more products exported by the Chinese or foreign supplier, essentially giving the US importer a discount on what it was buying before the currency was devalued. Having more products allows him to maintain his price in the US minimizing inflation and not having to pass on the tariff. Who then has paid the tariff cost? It is the exporter because the spending power of the converted 100 dollars he was previously receiving buys him less at home. The exporter nation, say China, forces him to convert his dollars into the local currency (the yuan remnimbi) and then holds the dollars so that the local producer does not buy $ imports with those same dollars. The next time he wants to buy something in dollars he has to convert his yuan at the lower exchange rate, buying him less than he would have been able to if he had used the same dollars. This is a form of currency manipulation called sterilization and it reduces the money supply in the exporter nation so that central banks can control inflation and exchange rates.

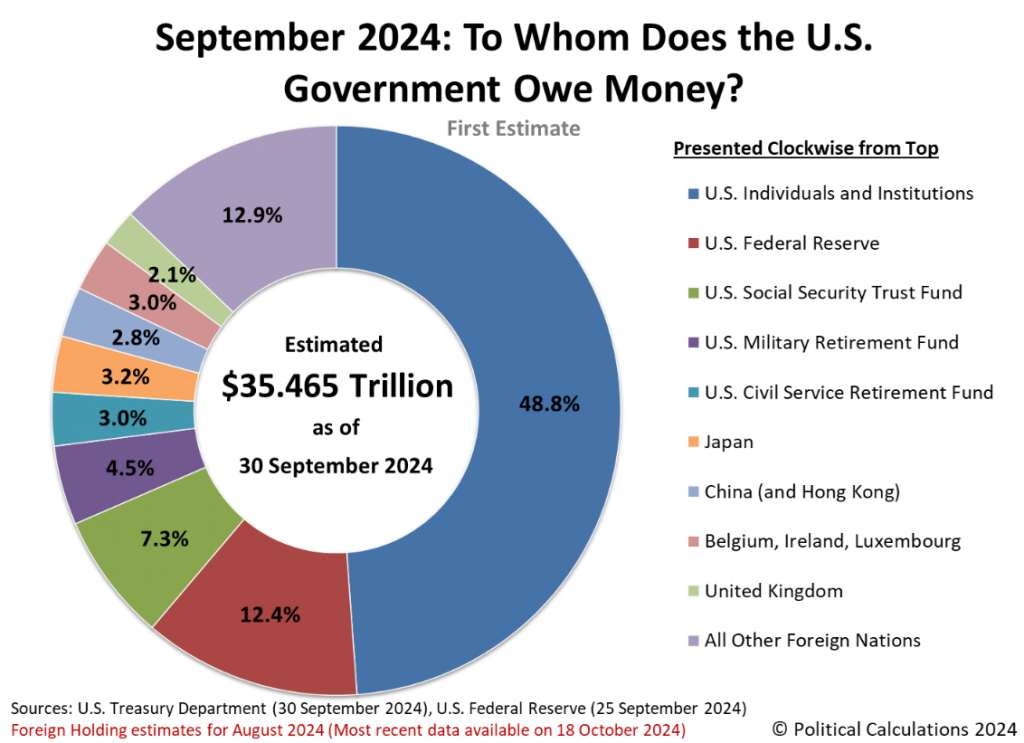

Now you ask who has the dollars? Well, the exporting country’s government has the dollars. On the one hand, they have saved their exporter’s competitiveness with this currency devaluation sleight of hand but now it must buy something with those dollars to earn interest, so it buys longer term 10 year US Treasuries, which gives it a very safe return. The more countries trade even with non-US importers ( say EU and China), the more US Treasuries they have because they essentially use their $ currency policies to subsidize their exporters. Most trade is done in dollars and many countries peg their currencies to the $. The biggest holders of US treasuries can be seen in the chart below.

So why is that a problem for the US, after all somebody is buying our Treasury debt? Well, the problem of having the world’s reserve currency is that we end up selling more debt to other countries than selling more exports of goods we produce. But surely, you ask, that is because we cannot make these exports more cheaply. After all, our labor is more expensive. That can be true but this does not apply to high-tech products with lower labour composition and products where we hold intellectual property. So, for example, there has been a lot of pharmaceutical manufacturing of US-developed products moved to Ireland, a lot of high-tech phone manufacturing moved to China and India, etc. Admittedly, it might take time to move that back to the US. Still, it is the currency and fiscal manipulation that has made those localities more attractive, not something inherently deficient in the US workforce capacity. Countries with equivalent labor costs also devalue their currencies to make their products more competitive. With all these countries then holding our Treasuries, the dollar stays high. Having the world’s reserve country therefore, has a downside that must be addressed. It offers trading partners a way to manipulate their currencies, as well as take advantage of fiscal benefits and lighter regulation, leading to cheaper labor. The playing field is far from level.

But I hear you ask, what about if they don’t buy our Treasuries, will we go bankrupt? This is important. Firstly, what would happen if those countries like China, Japan, and EU all started selling their $ Treasuries? The first thing that would happen is that their currencies would strengthen, making their exports uncompetitive- not just with the US but with all other countries. That is the problem this situation is trying to solve. Secondly, what would they buy with those dollars sold? If they bought Euros then the EU would be livid and the same goes for the Japanese or any other country because their currencies would rise making their exports more expensive. Thirdly, who would buy all these Treasuries if they were sold by the leading countries? Well, around 29% of the total stock of US treasuries is held by foreign nations, with China owning about 13%. If there were a huge exodus, which is very unlikely for the reasons stated above, out of Treasuries by foreign nations, the Federal Reserve would increase its balance sheet to acquire them just as it did during the 2008 crisis and the pandemic. It has since reduced the size of its balance sheet. That is why, as the holder of the US reserve currency, this unlimited Fed capacity not subject to any debt ceiling means the US can never technically go bankrupt. Of course, this does not mean that it is nerve wracking when there are bond market jitters, but the reality is that there are few options for people looking for an equivalent to the $. What is therefore, the better question, is can the US charge a premium for the use of US treasuries depending on what it is being used for. If as 70% of the Treasuries are being used for savings purposes they should be left alone but if they are being used for currency manipulation purposes they should carry a surcharge- that is in essence the currency plan here.

But to get to this point, the Trump administration must obtain leverage. The first element of leverage it has is its defence capacity and that will be put in place to force the hand of those needed, in particular the EU and East Asian nations like Japan. The second element it needs is momentum and it has that with the 75 nations at the negotiating table. Returning to the mainstream media message of this being an isolationist administration, nothing could be further from its interests and intentions, as this analysis shows. It is all stacking up as a way to isolate China rather than a way to isolate the US.

So, how are you going to know if this is the real plan and if it is working? Here is what to look out for. What the Trump administration wants is to pay less interest on dollars used for foreign currency reserves. How? Either get countries to buy and keep fewer long-term Treasuries so that there is less demand for the 10-year note except from US savers (leading to lower mortgage rates and Federal reserve costs), or charge the countries a fee for holding longer-term Treasuries, which has the same effect. They still want the dollar to be the lubricant to trade, but they do not want its proxy instruments like Treasuries, used to depress local currencies artificially in the way I described above. At the same time, this strategy makes it difficult or more expensive for the exporting country to devalue its currency. The tariffs, then, are a tool of the real war. This is not a tariff war with simplistic comparisons to Smoot-Hawley pre-depression, when the dollar was not the world’s reserve currency ( Bretton Woods 1944 was when it happened). It’s a currency war, or really a currency adjustment. Stay calm and carry on.

Resources:

- Steve Miran’s article A User’s Guide to Reststructuring the Global Trade System. https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:US:9cfc0dc5-c188-46e9-b266-3e3b5e470e40