February 26, 2024

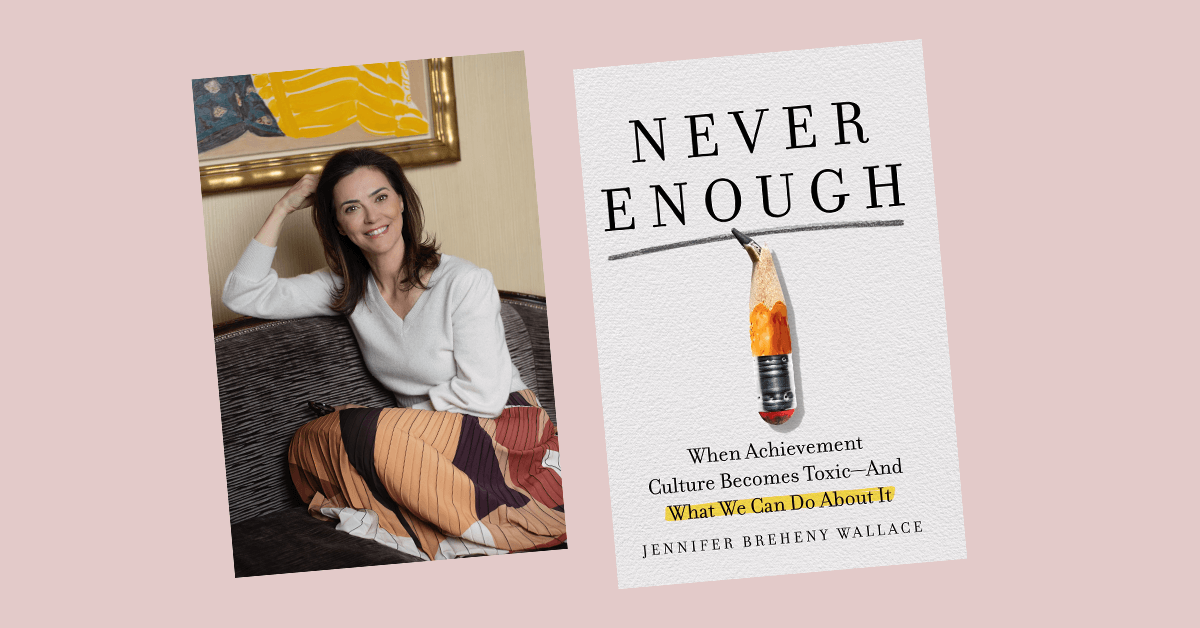

I recently had the privilege of speaking with award-winning journalist Jennifer Breheny Wallace about her new book, “Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic—and What We Can Do About It.” The title was enough to grab me and it ought to concern you, as it goes to the heart of the tension between what society conveys about achievement and what might actually be best for our kids. Are we measuring the wrong things? And is externally measured status becoming more important than intrinsic and organic development?

Wallace is a co-founder of the Mattering Movement, an initiative that emerged when a group of New York City leaders gathered to discuss rising concerns involving the mental health crisis affecting so many in their community. Wallace became interested in the skyrocketing rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness among students in high-achieving schools. In 2019, a national study labeled these children “at risk youth” for the relentless pressure they experience. In the introduction to her book, Wallace calls it an “unsettling paradox” that “students who are afforded every opportunity were statistically more likely to experience worse outcomes than their middle-class peers according to tangible measures of well-being.”

Well-resourced public and…