April 10, 2024

Background:

As I was burning out at my last independent school job before COVID hit, I was searching for better ways to work in school, both at the classroom level and for the rest of the school. I found L-EAF in the Spring of 2020 via the Boston University Agile Innovation Lab Executive Board on which I sat. I got trained by the founder of L-EAF, Jeff Burstein, and continue to get coaching from Jeff on a regular basis as I and my collaborators continue on our mission to make school more joyful, rewarding and effective for all who work in or go to school.

For four years I’ve used L-EAF’s LearningFLOW pedagogy and WorkFLOW methodology in the following contexts with over 300 learners:

- University level: domestic and international, both professors and students.

- High school level: domestic, public and private, both students and faculty.

- Middle school level: domestic, public and private, both students and faculty.

Before running into the Learning Educational Agile Framework at L-EAF.org, I’d been trained in Understanding By Design, Socratic seminars, abd Scrum, and had two decades of experience in student centered, project based learning at independent schools in the Northeast. I’d been most influenced by John Dewey and Lev Vygotsky and thought there was really nothing new under the sun. I was wrong.

With a wide range of applications and four years of experience to reflect on, I feel confident enough to undertake a retrospective on this no-longer new kid on the pedagogical block. What follows is a summary of the pedagogical approach as it stands now, why and how it works, and what other educators might try if they are curious about the approach.

The essence of this pedagogy starts from a simple premise: student engagement in their learning increases as they are allowed choice in certain aspects of their education. This is accomplished through revising an assumption found in most schools and held by most teachers: that the teacher is the right and full owner of both the curriculum and the pedagogy. What makes LearningFLOW act like a magnet to learning in any environment is that it builds on what Dewey, Vygotsky, Ted Sizer, Alfie Kohn, Vivian Gussin Paley, and tons of other educators have known all along: that the education game is, in the end, about students and change.

L-EAF’s pedagogy adjusts the learning environment in one way: it allows students access and voice in the ‘how’ of the learning process—how the knowledge is acquired and demonstrated.

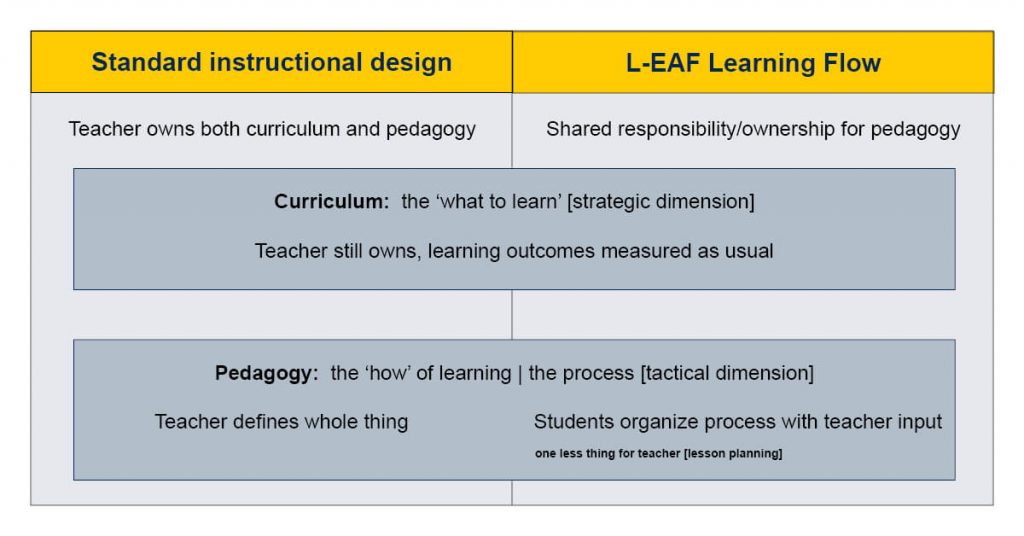

To make a direct comparison between L-EAF and the general world of practice we see around us, the below makes the distinction without judgment or assessment.

As an example, when doing a unit with local sixth graders on body systems, I started by introducing a learning objective based on state content standards. Rather than the students just running to grab their tablets to start researching and taking notes with abandon, we took the time to talk about why learning about body systems mattered in the first place. Students shared with each other, listening to what others found significant. Then I guided them into conversation about how they would want to demonstrate their knowledge, what the pros and cons were of their ideas. Again we started the unit a bit slowly, building interest and learning tension so we covered purpose and outcomes before getting into content. Once they were ready to get into action they quickly made their daily work plans, got their commitments into their LearningFLOW work boards, and got to work. What happened next was an unusually quiet and focused three weeks of engagement. Students talked to each other more, but the conversation was about work. My time became about unblocking students when they got stuck, facilitating and guiding as needed. Because they owned the daily learning plans, I didn’t need to be directing the action outside of occasional reminders.

When teachers begin to unglue the strategy and the tactics, the curriculum and the pedagogy, they find that they have literally one LESS thing to do—lesson planning. By breaking the monopoly on learning design, teachers share some responsibility with their students. They unlock the energy students have in their nature as learners by giving them choice in ‘how’ they learn. As someone who grew to enjoy lesson planning less and less over time, the ‘one less thing’ is actually much better than just that. It represents one more thing for students, something they often report missing in school: any combination of autonomy, purpose and opportunity. We all should be so lucky. And as school people we are.

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Simon Holzapfel for Intrepid Ed News.