April 29, 2024

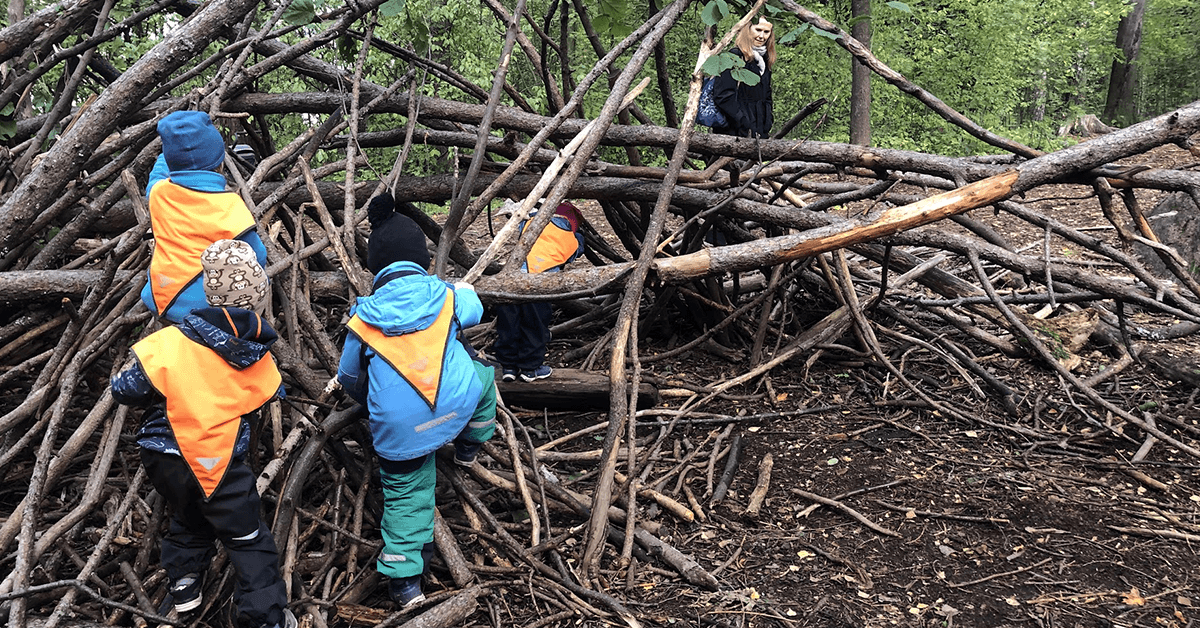

Why do we tell our children to finish their homework before they play outside? Why, for that matter, do we so rigidly distinguish between work and play, inside and outside, an academic curriculum and time spent in nature? Why can’t learning involve a science lab and a walk in the woods?

If we need researched reasons to break down the false dichotomy we’ve developed between free play and cognitive development, we need look no further than Jonathan Haidt’s justly popular new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Haidt argues that a phone-based childhood has replaced a play-based childhood to the detriment of children’s well being. He sees outdoor activities like recess as an important way to foster resilience and independence in kids. Not only does playing outside promote kids’ physical health, but it also promotes their social skills and academic achievement.

I’ll fully discuss Haidt’s terrific book — which more generally and masterfully takes down our phone-driven culture and what it’s doing to our kids — in my next column. But with the onset of spring and warmer weather, I’d like to…