January 29, 2024

The central question keeping me up at night as an educator is this: How can we maximize every student’s potential? This question emphatically isn’t about making sure a student becomes “the best” at anything in particular, but rather about ensuring all students become their best selves.

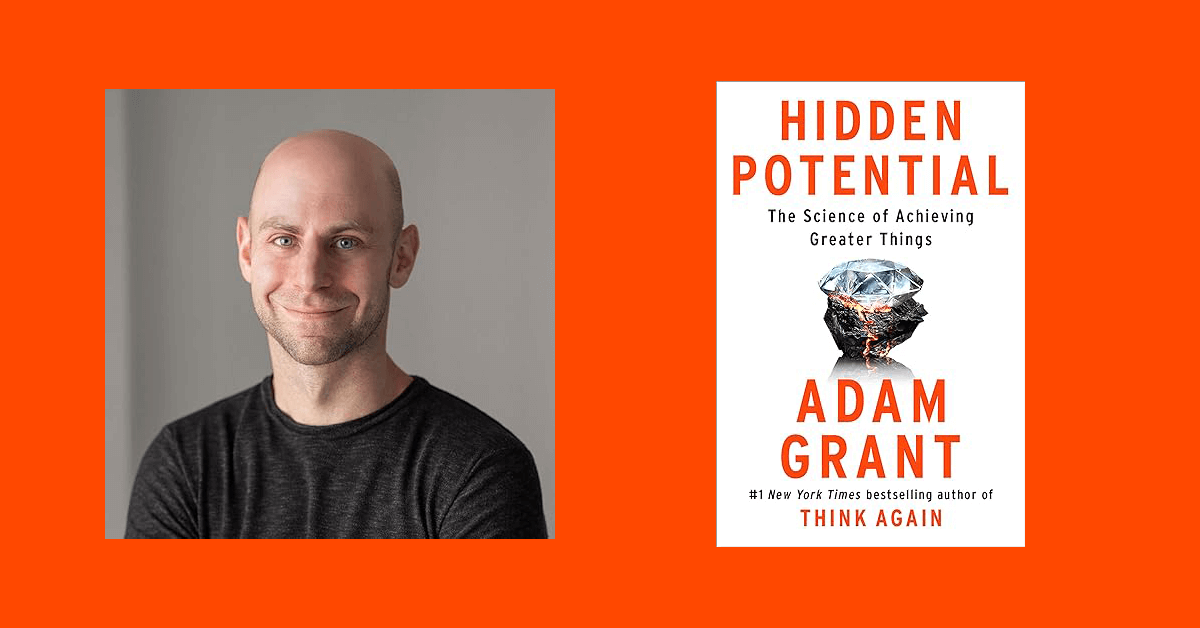

In his new book Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things, Wharton guru and organizational psychologist Adam Grant explores how we might maximize our potential in ways that are highly relevant to our middle schoolers. In middle school, students are still learning how they learn and discovering their interests. In some ways, middle school is the perfect time to put Grant’s strategies into practice.

Essentially, Grant makes the argument that anybody can learn almost anything if they are provided the appropriate conditions for learning it. Grant persuasively demonstrates that people achieving great things are not “freaks of nature” but rather “freaks of nurture.” His research serves as a handbook for unlocking potential and creating opportunities for self-growth. He also offers some surprising truths that challenge traditional beliefs about learning and leadership. For example, competition and comfort actually inhibit personal growth. Yes: you read that right.

I urge you to…