May 28, 2024

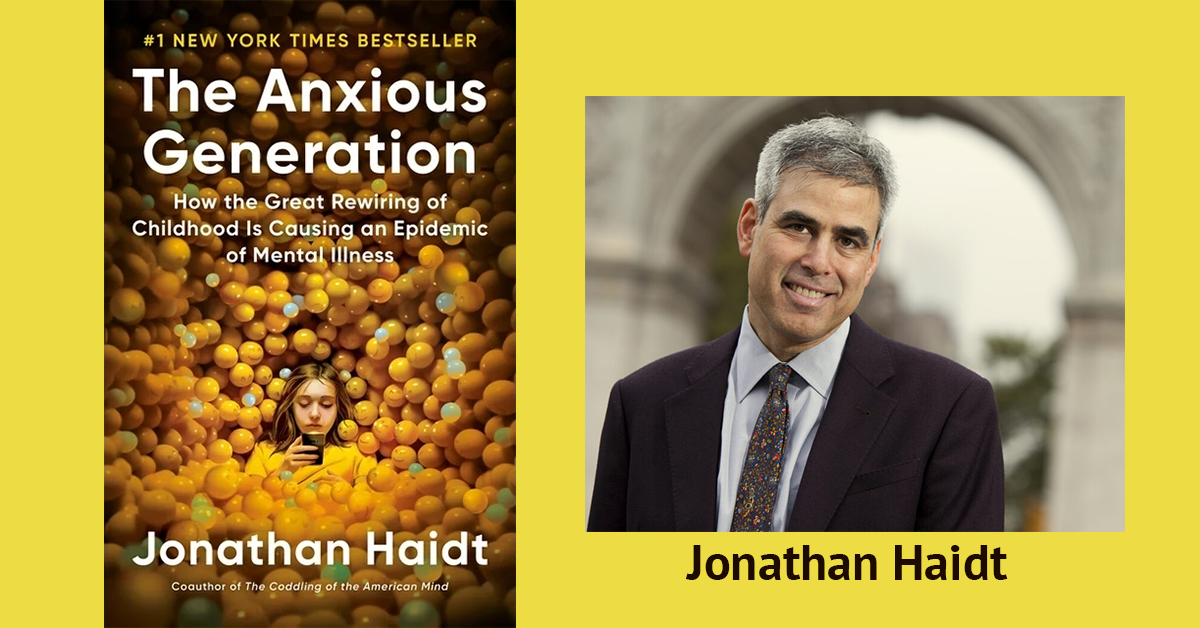

In Jonathan Haidt’s justly acclaimed new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, he repeats a Polynesian expression: “Standing on a whale, fishing for minnows.” Haidt explains that “sometimes it is better to do a big thing rather than many small things.” What’s the “big thing” Haidt wants to do, which has catapulted his book to number one on the New York Times bestseller list?

Ban smartphones so that we can save our kids from themselves.

Banning smartphones, a big thing, is especially important in the middle school years. At the onset of puberty, children are particularly insecure, heavily influenced by social pressures and easily persuaded to participate in activities that lead to social validation. This makes the price of using social media high for these students—much higher than for adults—while the offsetting benefits are meager.

As children develop, Haidt explains, they have “critical periods” when they “must learn something, or it will be hard if not impossible to learn later.” For example, there is a critical period for learning a new language: from childhood to the beginning of puberty. When children move to a new…