March 25, 2024

For latchkey kids like me growing up in the 1980s, teenage angst was a collective character trait. Popular songs like “Don’t You (Forget about Me)” by Simple Minds or “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by The Clash channeled our moodiness and insecurities. Movies like Footloose and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off explored teenagers’ rebellious instincts while their parents were off-screen and out of the loop. Growing up is hard, the entertainment industry told us, and our experiences confirmed that.

In 2023, kids are being schooled by the wellness industry, which now represents a larger segment of the global economy than the entertainment industry. These young people should have a much better chance of growing up happy than we did. But do they? And is it possible that the pursuit of happiness is itself part of the problem?

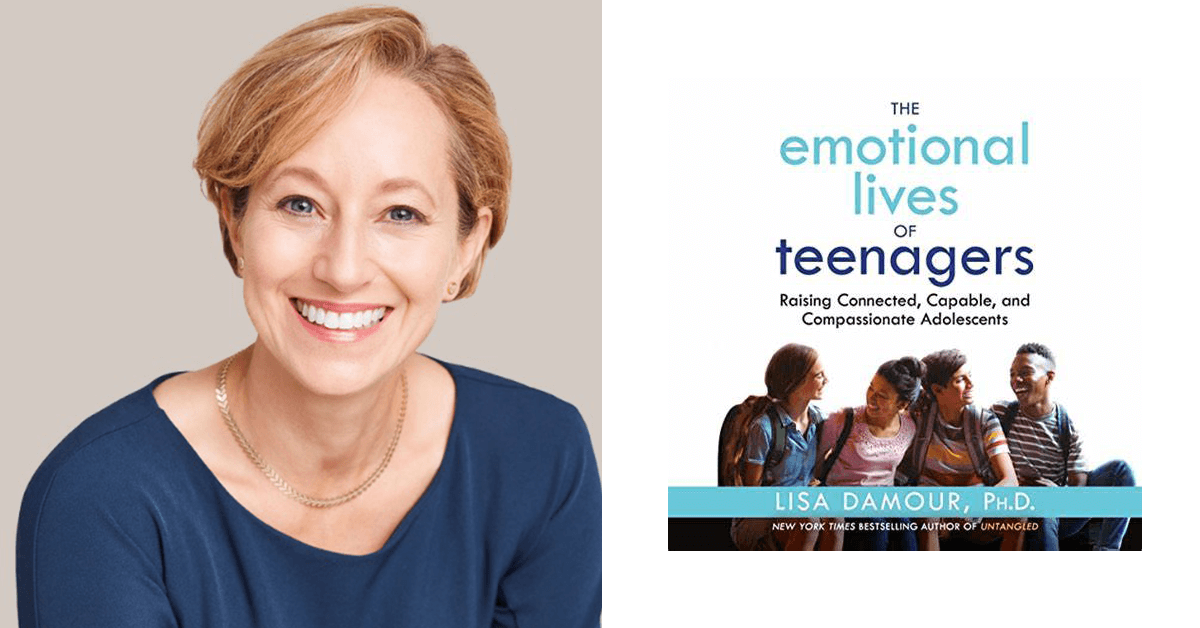

In her insightful new book, The Emotional Lives of Teenagers: Raising Connected, Capable, and Compassionate Adolescents, clinical psychologist Lisa Damour argues that the wellness industry has contributed to a new cultural norm that simply isn’t sound or even useful: it has equated feeling good with mental health. The result, Damour asserts, is that we are “afraid of being…