Observations from the Classroom and the Teacher’s Lounge

Background:

Students have been consistently trained to listen to teachers, both because the teacher knows important things like key content and because the teacher is a gatekeeper to a grade outcome. Students have been generally trained to believe that teachers have all the answers relative to the course they are teaching. John Taylor Gatto and others have described the complexities of this training, especially the costs to democratic deliberation and other civic goods. At the same time, we also know that a classroom without a teacher present and in charge can quickly become unsafe — not what school is designed for.

Current Condition:

While schools have taught a particular sort of student-teacher interaction and expectation set, students are entering a world where, both in professional and personal contexts, the ability to critically and creatively solve problems, collaborate and experiment is increasingly essential for success. This creates a tension between what is ‘normal’ in school and what is needed after school: a conflict over what the teacher should be doing now in their interactions with students, versus what sort of interactions would be best to set that student up for future success in a complex world.

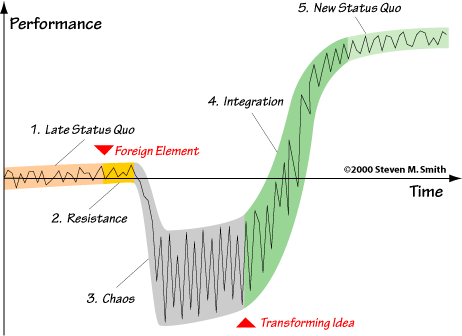

Jessica Cavallaro and others in the L-EAF.org community of educators have written extensively about how teachers can resolve this tension. If you are considering taking a leap into educational agility, the below will give you some things to expect when you’re expecting to change your pedagogy. Educational agility introduces new dynamics to student-teacher interactions because it relies on students to supply new inputs to the classroom environment. In particular, educational agility requires a teacher to introduce limited forms of uncertainty as a learning opportunity instead of a threat.

Helping teachers who want to make their classroom environment more student centered prepare for what that will look like on a day to day basis as the students learn and practice a new way of working is the primary goal of LearningFlow. Welcome to the first microcycle of LearningFLOW in your classroom. Get ready to roll up your sleeves and say things you maybe haven’t had to say before, such as: “Go find out” or “Get some options” or “I’m not sure”

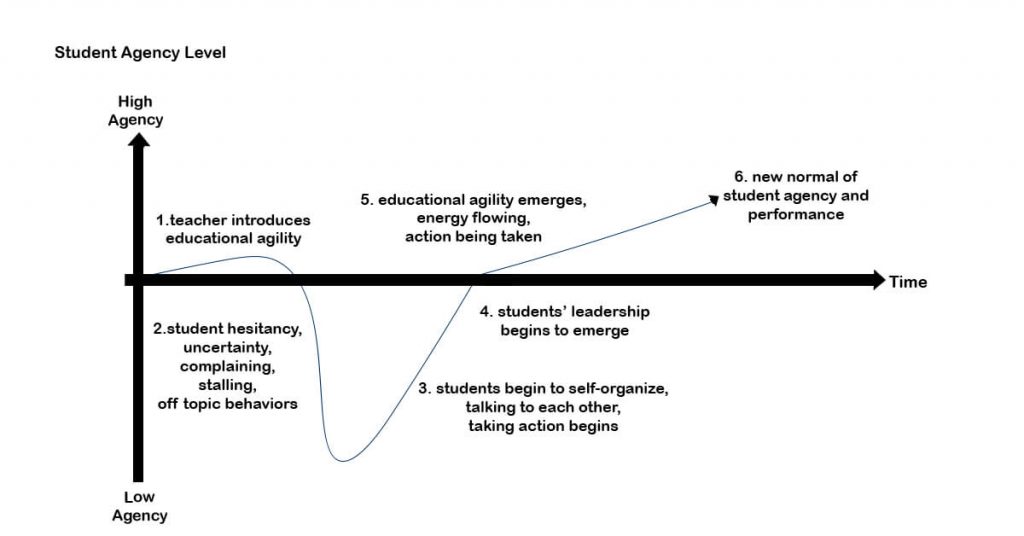

The Journey to Self-Organization

Starting on the left and reading right, you’ll see in order:

- Business as usual time, before the educational agility pedagogy introduced. This assumes you’ve already done enough unit planning planning to have one learning goal [a learning standard or outcome described] created and visible to the students to start working on, usually on a learning board. Before getting to this point you should also have formed the students into teams and each team should have some sort of team agreement specifying how they will work together.

- When you introduce the first learning goal it will not tell the students exactly what to do next. They might not like this, or at least all of them probably won’t like it. Be ready for students to lapse into old ways of organizing themselves. They might shut each other’s ideas down too early. They might start telling each other what to do. Normal levels of disagreement and uncertainty will exist as the students figure out how to work in a new way and organize how they will purse the learning goal. This is fine and will take time and is where the teacher needs to serve as a coach and facilitator. Resist the temptation to solve their issues too early or get drawn into their dynamics.

- Some students may be reactive enough to conflict or disagreements that they disengage. Don’t abandon them. You can ask them what they are seeing if they are spectating others’ discussions. You can ask them if they have ideas about what is going on. You can show them they still matter to the process. Be brave with them.

- At some point the team will start to gel. The level of leadership and agency within the group will build to the point that students start to show self-direction and self-organization. With any act of leadership and self-direction you can reinforce or celebrate that. Don’t go overboard with celebration. Keep the feedback direct and positive as they pull through the “storming” phase every self-directed team goes through eventually.

- The time to get card #1 done will be longer than every card after that most of the time. As you get better with calibrated choices in the classroom and the new norms emerge about how the students will accomplish their learning goals, the conflicts will become more about the substance of the work and not about how the work will get done.

- The team moves out of the ‘storming’ phase and into the ‘performing’ stage and the flow of work improves. You’ve crossed the chasm of student passivity into the land of genuine student agency.

The classroom management adjustment you need to make in supporting your students’ educational agility will be mostly about getting the group to listen and share ideas with each other. Some groups can get to work pretty easily. Others will expect the teacher to tell them what to do, because they are used to that. Most important is to not worry about how fast they get the first steps done and into action mode. If you let the pressure to stick to your content timeline drive your classroom management, your students probably won’t have the time they need to learn a new way of working and learning. The pace will pick up. (You may also be interested in reading Jessica Cavallaro’s articles about classroom success written for Intrepid Ed News.)

Conclusion

If you decide that an experiment with educational agility is right for you, be ready to rethink classroom management. Empowered students change how they learn and they change how the classroom works. They will need different things than before — which will allow you to change along with them if you want to. Learn on!

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Simon Holzapfel for Intrepid Ed News.