June 28, 2023

In Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, 11-year-old Margaret learns a chant and exercise from her friend Nancy, the queen bee of 6th grade, that nearly all readers will remember. Making fists and bending their elbows back and forth, the girls recite, “We must—we must—we must increase our busts.” They believe that doing this exercise 35 times per day will produce results.

And you wonder why Margaret was tantamount to contraband at my Catholic grade school in the early 80s? It mentions all the taboo subjects for girls on the cusp of puberty: periods, training bras, and the first kiss.

We didn’t dare talk about such things in public. But we were obsessed with them in private, in an era before social media when privacy still existed. More on that in a minute.

Prior to seeing the recently released and excellent film adaptation, I reread Margaret. It was—it is—a time capsule from my childhood. I was in 6th grade again, curious about and embarrassed by my changing body.

If classics are defined by their continuing relevance when it comes to speaking human truths, Margaret joins Blume’s other works in making the grade. That may explain why her books have sold more than 80 million copies to date. And why, living as we do in a world that in some ways is lightyears removed from the 1970 universe in which Margaret was published, Blume’s classic nevertheless remains relevant today.

To be sure, the details of Margaret’s suburban New Jersey childhood can feel remarkably innocent today; running through a sprinkler on a hot day suggests a nearly vanished world in which summers actually were lazy.

But while the particulars may have changed, Blume’s ability to successfully and precisely channel that nebulous time between being a child and being an adolescent—a time of shared secrets involving first crushes and changing bodies—still rings true.

Blume delves into the significant “firsts” of adolescence time and again within the book; Margaret’s first bra, the first box of maxi pads, and the first kiss are all explored in detail. Each experience is made visceral on the page, as Blume never shies away from the excruciating awkwardness associated with each moment.

Here’s just one illustrative example involving Margaret’s purchase of her inaugural bra:

“First we went to the ladies’ lingerie department where my mother told the saleslady we wanted to see a bra for me. The saleslady took one look and told my mother we’d be better off in the teen department where they had bras in very small sizes. My mother thanked the lady and I almost died.”

Because Margaret feels so vulnerable, she shares her innermost secrets with a secret friend whom she calls God; regardless of whether one is religious, her supplications endear her to us because they recall a time when we were developing our inner voice, that self-conscious “I” with whom we collaborate in fashioning the self and with whom one is in dialogue when talking to oneself.

Margaret confesses that she’s scared to move out of the city to New Jersey. She asks God to accelerate the timing of her first period, as she desperately wants to fit in and keep up. She even asks God for breasts: “I’ve got a bra now. It would be nice if I had something to put in it.”

Many of Margaret’s prayers prompted me to laugh. But others were poignant. And all of them made me nostalgic, less for my Catholic girlhood than for a time when all of us took the time to listen to the sound inside that helps us learn to sing the song defining who we are.

The new movie portrays Margaret’s vulnerability beautifully. It also captures the humor and grace with which Blume treats Margaret’s questions and mistakes. The movie’s popularity speaks to the universal experience of adolescence; anyone who’s gone through it knows it’s a time defined by heightened emotions and self-discovery.

At the same time, Margaret’s highly developed interiority—that increasingly mature inner voice through which she learns to reflect with greater self-consciousness and awareness about the world—also suggests something we’ve lost between 1970 and today.

Margaret is anchored in a particular place and time, one free of the technology that has irrevocably altered the experience of growing up. Margaret’s friends knock on her front door or phone her family’s landline when they want to talk. Margaret walks to school. She writes letters (in cursive!). Most important, God can be Margaret’s confidant because she lives in a world that still has gaps of silence within the day that allow for reflection. She’s not constantly online, and she’s not compelled to always be “on.”

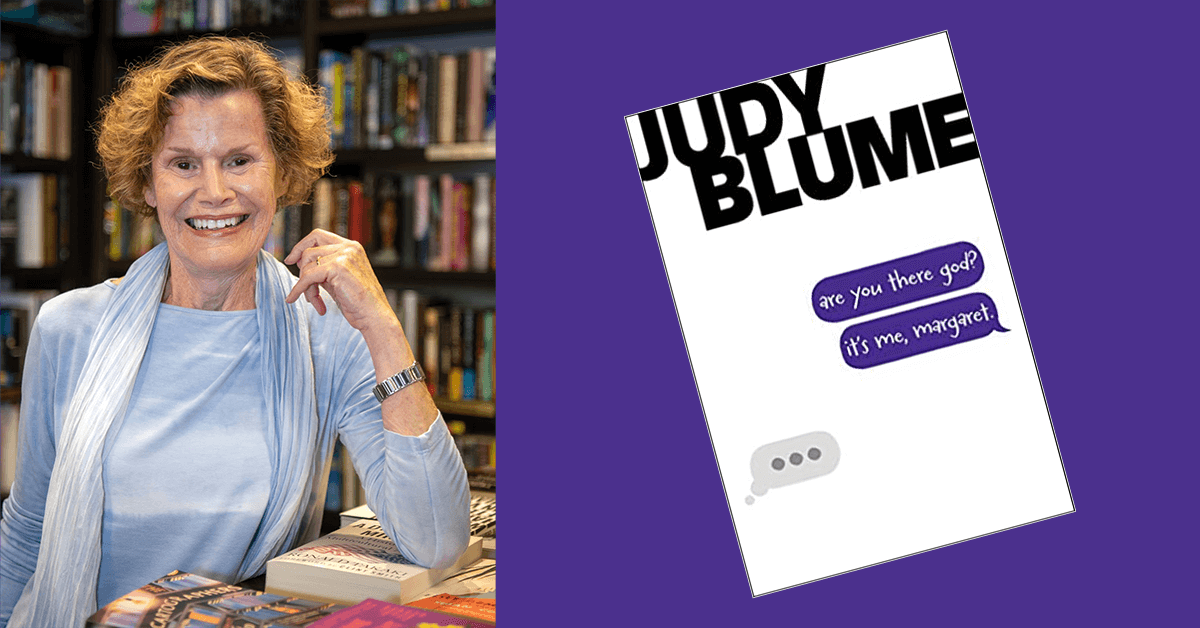

Perhaps this is why I find the book’s current—decidedly anachronistic cover—so false. Displaying the title of the book as a lowercase text bubble to God—are you there god? it’s me, margaret—represents a disingenuous attempt to connect an old book to the current moment in which kids are growing up immersed in technology, a moment that leaves little time for the self-reflection characteristic of Margaret and her friends.

Failing to accurately measure all we’ve forsaken as a result, such elisions of the profound differences between then and now—the Margaret of 1970 and the Margaret of 2023—do Blume and her book a disservice, while potentially underestimating or entirely missing the challenges current tween and teen girls confront.

I don’t know what it’s like to grow up with the “always on” culture of texting and the “compare and despair” culture of social media. I feel lucky to have escaped it all, and with good reason: the new U.S. Surgeon General’s report about the harmful effects of social media on young people drives home what I’ve repeatedly stressed in my column regarding all we’ve lost through some of our tech “gains.”

In the recent documentary Judy Blume Forever, Blume says of Margaret, “I felt I needed to write this book . . . I wanted to write the truth, the reality of being that age.”

Blume did, much as Louisa May Alcott had a century earlier with Little Women; both books will live forever precisely because they’re so good at channeling that precarious but also exciting moment betwixt and between when girls become women. It’s a testament to their greatness that they can still speak to us, despite our many differences from the times in which they were written.

But we don’t do Blume or Alcott—or the tweens and teens reading them—any favors when we deny all the ways the world has changed between then and now.

Margaret captures the truth of the adolescent experience and the reality of growing up in the 1970s. When we read Blume’s book we are reminded of those universal truths as well as the unique historical moment of her character.

Reading with such double vision doesn’t limit a classic, but extends it—reminding us of all we share with the past, while also taking the measure of what we’ve lost, living as we do in a world where we text more and reflect less.

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Elaine Griffin for Intrepid Ed News.