October 24, 2023

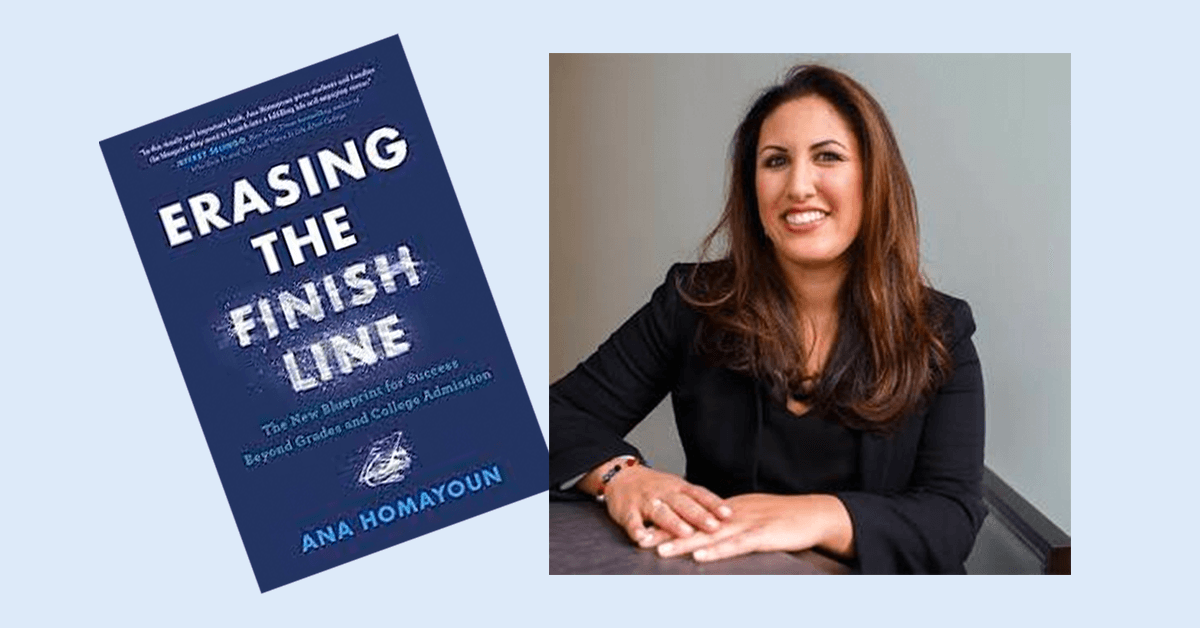

Newsflash: Getting into college shouldn’t be any child’s central goal. Or so says Ana Homayoun in her new book, Erasing the Finish Line. I emphatically agree with her.

“The false finish line created around college admissions,” Homayoun contends, “is not just exhausting and misleading; it is fundamentally crushing the social well-being and emotional development of our kids.”

She should know. As the founder of Silicon Valley’s Green Ivy Educational Consulting, Homayoun has worked with thousands of students navigating their way through middle school and high school as well as through the college admissions process.

Her experience has convinced her that the emphasis on college—which encourages students to focus on external markers like grades, standardized test scores, and extracurricular activities—creates a one-size-fits-all mentality. Homayoun has a better idea: Students should become “the architects of their own futures,” making choices that nurture their own interests, creativity, and leadership abilities.

By focusing on “skill building” rather than “resume building,” Homayoun has seen her students far exceed their initial goals. When elementary and middle school students cultivate foundational skills—developing good study habits, fostering interpersonal relationships, and practicing self-advocacy—good grades often take care of themselves. If students don’t develop these skills before high school, they may struggle through their teen years and into adulthood.

It can be hard to get parents and students to appreciate the value of such a long game. Many students come to Homayoun seeking help with immediate needs, such as an essay or math homework. Rather than fixating on such short-term goals, she works with each student to create a comprehensive approach involving organization, planning, and problem-solving that will serve them in all subjects.

Homayoun’s approach “enables a fundamental shift from what we learn to how we learn.” Such a systematic process is even more important in our age of technology, which deluges students with short-term distractions that erode attention spans and make perspective difficult.

Here is some of Homayoun’s most compelling advice on ways to ensure that your tween or teen has the tools to design their own blueprint for success.

Create a System to Support Schoolwork:

When students enter middle school, they go from having a single teacher and classroom to having multiple teachers and classrooms. To make matters more challenging, their brain’s prefrontal cortex, which manages executive functioning skills, is still under development. Homayoun writes that “beginning in middle school, we wrongly assume students can figure out their own systems, without the time, structure, and support they need to do so.”

Students must learn how to organize their binders, keep an assignment notebook, and complete assignments without distractions. Creating a nightly study plan that includes breaks and movement is important. Even if a student can only study for 15 minutes at a time, that’s okay. Habits build stamina, and once these habits are “second nature, students can find themselves expending less energy on getting started and more time and energy focused on completing the actual work.” Homayoun has a mantra she repeats for students: “Focus on the habits, not the grades and scores,” because “if you focus on the habits, the rest will come.”

Cultivate Interpersonal Skills:

Homayoun makes a great case for developing interpersonal skills amidst the “growing epidemic of loneliness that’s severely impacting kids from middle school onward,” as “social media terms like ‘friending’ or ‘following’ or ‘being connected’ … distor[t] our understanding of what connections mean.”

Bucking the notion that a student’s popularity should be based upon social status and power, Homayoun encourages her students to focus instead on likability, a quality “rooted in authentic connection.” This is especially important in middle school when students are maturing at different rates and outgrowing friendships quickly. Because the transition between friendships can be a lonely time, kids need friend groups in different areas of their lives. Homayoun suggests that kids take on “a floater mindset” and move among friendship circles that might include neighborhood kids, school friends, and teammates. When struggling with one social group, they’ll have others to rely on.

Expand Perspectives:

Kids need to expand their ideas about what constitutes success and grasp that there are many paths toward building a life of purpose and meaning. By seeing that there are multiple perspectives in the world, “students can experience greater self-acceptance and a deeper sense of worth.”

Homayoun believes the most powerful way to cultivate perspective is through “immersive exposure.” Working as a grocery store bagger, for example, pushes students to interact with the general public and make small talk with adults. Doing service work engages students in the lives of historically underserved communities and broadens their worldviews.

Develop Acceptance:

When kids are little, they accept who they are and love sharing what they like and want to do. But this authenticity and openness can fade when kids hit puberty, as they then try to behave in more socially acceptable ways. In our achievement-oriented culture, that means kids are more likely to judge themselves according to external achievements.

Adults can support the children in their lives by helping them recognize their internal gifts. We can nurture such qualities—and simultaneously foster a higher level of social and emotional maturity—by encouraging kids to accept and value themselves. “It’s about helping each person honor their gifts, talents, and interests while encouraging them to identify areas of growth.”

It’s important for parents to learn their child’s energy profile and respect it. “Orchid children” are sensitive to noise and need downtime after being in stimulating environments, while their counterparts, “dandelions,” are less reactive to stressful environments. These two types of children may be in the same family.

All children need time to rest and recharge their batteries. When kids are overscheduled, they don’t have time for personal reflection or imaginative play—two tools that enable them to figure out who they are and what they like to do.

Celebrate who kids are as individuals and support what they need. Doing so will reduce their anxiety when learning new things and encountering challenges. Conversely, kids who are constantly trying to become “good enough” are prone to burnout and overwhelm.

Be Aware of Energy Allocation:

In her book, Homayoun uses the term “taking the B,” which stands for something that needs to take the back seat to other priorities. It “is a metaphor for living a life of acceptance and, in the process, overcoming the culture of perfectionism and the never-ending list of to-dos.”

In terms of time management, Homayoun points out that the verb “taking” indicates that we are making a conscious choice when we decide to let something take a back seat to other priorities. We all have limits to our energy, and it’s okay to be discerning about how we spend our time; making choices is integral to being human. The activities that take a back seat may depend on the seasons and the various sports, academic projects, and family commitments students have.

Having a flexible mindset, and learning to prioritize rather than trying to do it all, not only helps students learn to manage time. It also challenges them to think about how they spend this most precious commodity—and what this says about who they are.

The alternative is burnout. And not just for teens, but for all of us, because we failed to learn how to take the time we need to be our best selves.

It’s Never Finished:

No wonder, then, that Homayoun concludes people are happiest in their careers when doing things that they enjoyed in middle school and high school. Students who learn to build their own blueprint “work toward goals that feel in alignment with who [they] are”—knowing that those goals will change as they do.

Overscheduled kids in prescriptively programmed activities may never discover what they really love—or even who they really are. Figuring out what brings an individual child joy is “an organic, sometimes circuitous process that takes time, exposure, and casual exploration.” It can be “anxiety-inducing” when we tell students to find their passion, as if they need to initiate a search for it. It can be equally exhausting when we tell them to participate in a host of activities to become “well-rounded.”

But by allowing kids the space and time to figure out who they are and what they like to do, we are providing them with the tools to be successful in their lives beyond high school and college. We are celebrating that “there are many ways to put a life together.” Most importantly, we are underscoring that one’s goals can and should change as one evolves.

Both our kids and we ourselves can best discover new places by having the courage to be lost. You never know what you might find.

While reviewing Ana Homayoun’s book, I caught up with her during her book tour to pose some questions prompted by my reading. Characteristically generous in her responses, she talked about why she wrote the book, how the book supports tweens, and her belief that our achievement-oriented culture really can change. Her responses have been edited for clarity and concision.

1. What compelled you to write a book on this particular topic right now?

Working with students for over two decades. I’ve consistently seen how parents, educators, and students have become convinced that acceptance to a “good” college is a ticket to lifelong success, and how this hyperfocus creates an underlying fear and anxiety for both adults and kids. At the same time, I was hearing how many students from 15+ years ago were using the same skills that they learned in my office in their work and careers, and how their success was often based on skills that moved beyond any grade, test score, and college admission.

2. What is the most relevant advice within this book for tweens and their parents?

All of the book is relevant for middle school kids and their parents, but particularly the section on systems.

I’ve always encouraged students and families to focus on the underlying daily habits and routines, believing when you do so, the grades will come. In elementary school, we generally provide more time, structure, and support to help students establish routines. When students start middle school, they are often tasked with juggling multiple different classes, each with varying short- and long-term expectations. Then we layer on different technology requirements and ways of assigning and turning in work, along with extracurricular activities and family obligations. Asking more than their still-developing brains can manage, students often disengage—consciously or subconsciously—believing that opting out is emotionally easier than constantly feeling frustrated and unworthy. I’ve seen firsthand how we critically underestimate the crucial underlying importance of helping middle school students develop a system rooted in strong executive function skills.

3. How hopeful are you that we can have societal change around the culture of achievement and the focus on college admissions?

The reality is that it takes time and concerted effort to change our individual and collective relationships to this culture of achievement. As I often remind parents, none of this skill-building happens overnight, and yet I’ve seen how daily strategies and habit formation have the potential to change the trajectory of students’ lives.

I also remind people that the current methods of “getting ahead” aren’t truly working for anyone—even those who are well-resourced and have great access to opportunities. A crucial part of my book, as well as my own work, is the conviction that all students deserve to create their own unique blueprint, which requires rethinking our very definitions of success. Although this journey may not feel easy in the beginning, the possibilities it will open up are greater than we can even imagine.

This all brings me back to why I wrote the book. I remember how so many of my former students whose stories are featured in the book were so stressed out about their college admissions process, thinking that it was some sort of magical finish line that defined their sense of self, their character, and their worth. And none of that is true. Visiting them all these years later, and sharing their stories alongside the stories of current students and research, helps illuminate the fundamental skills we should be focusing on to support our children’s long-term success and overall well-being.

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Elaine Griffin for Intrepid Ed News.