January 14, 2025

This keynote address, adapted here as a 30-minute narrative meditation on silence, was delivered at the OESIS Annual Conference in Quincy, Massachusetts, on October 27, 2024.

“This stillness and quiet and repose of the soul are a great blessing.”

St. Teresa of Avila

When was the last time you put your mind and heart into something—when your mind and heart were completely aligned, and became the same? Full immersion, the experience of your soul.

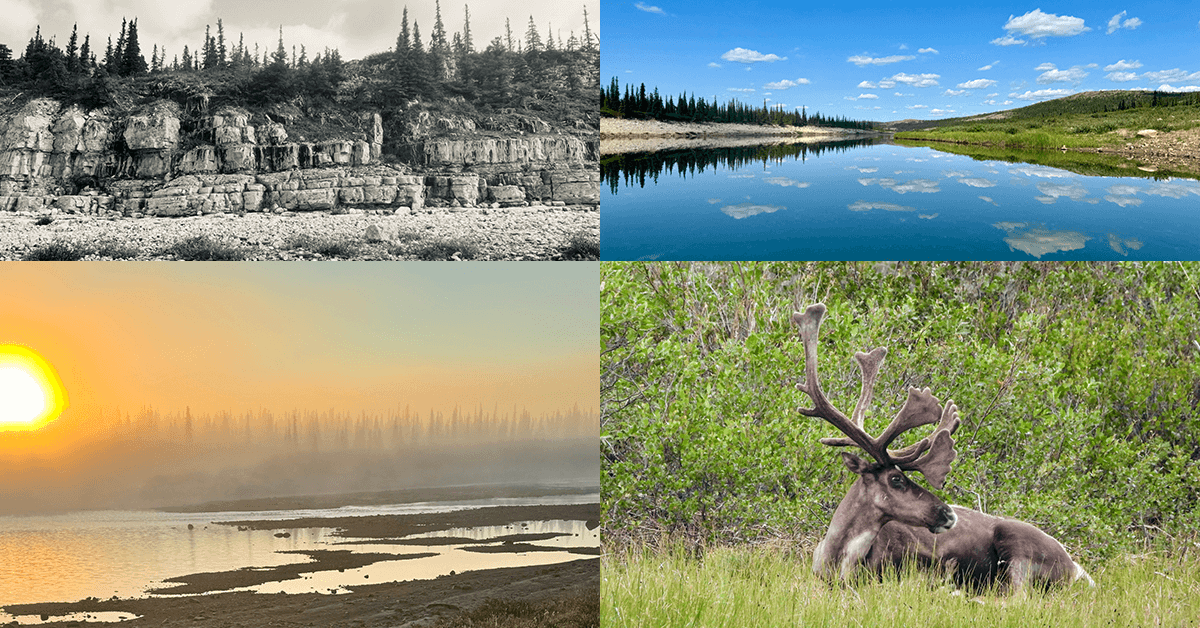

Not long ago, I traveled to one of the remotest places on the planet, where no humans are known to be for many miles. Here, the caribou and perhaps the grizzly bear or wolf hear your whispers, smell your tent or canoe downwind, and hear things we have long stopped hearing. That hearing calls for a sensitivity to the natural world that may be considered anachronistic: most humans are in cities and hear almost nothing that is not manmade or man-caused. And as teachers, most of our students are in classrooms, laid out in squares over concrete. We fill in the rest, in ways that are hard to describe a soul, but maybe we can get there.

Teachers are routinely left feeling the need to fill every pause and emptiness with words, as though words replace all other sensitivities. As though learning and words are the same.

In our schools, we come to understand that silence is a thing to be broken, although, like soul, no one seems too certain what silence is. But when we produce the right environment for the lack of sound, and accept it, silence seems to become a powerful space for reflection, letting students absorb what they’re experiencing. In that quiet, a deeper, immersive learning can take root within all of us.

In that quiet, we can become attuned to the unspoken connection between ideas, between one another, and to unseen forces of nature. We can enter a kind of flow, or “zone,” which could be: silence.

All the same, teachers and students often feel uneasy with silence, even when they know it can lead to deeper understanding if internalized. It feels like uncharted territory—an Arctic expanse—and rather than looking around us, we focus on finding a map. Retreating into the AI world has become natural and automatic, where we habitually and comfortably can be filled with streaming guidance, often while barely even seeking it. We must fill any emptiness. Now.

Meister Eckhart’s concept of via negativa is an approach to understanding God or the great mystery or the divine. He realized this by removing all human concepts, names, and attributes. The ultimate reality for him lay beyond human comprehension and description. The process of experiencing that reality involves a kind of emptying or letting go.

This story explores the power of quiet in deep learning, aiming to inspire reflections drawn from personal moments of focus and eureka. Here is my story from a recent trip, in six parts:

Part 1: Beginning in Silence and Immersion

The first landing point in the Canadian Arctic is often Yellowknife, the largest town in the vast Northwest Territories and a staging area for much of the region’s gold and diamond mining. From there, after a mug of Bug Repellant IPA beer, we set out, and my party of 10 canoeists would not see a sunset for three weeks.

We flew a few hundred miles to the town of Norman Wells, population 736, to pick up canoes and were floatplane-dropped onto a small lake around the 66th parallel, the southern boundary of the Arctic. There, we set up our first camp.

The idea was to paddle through a remote wilderness, free from the distractions and definitions of the civilized world, to let go of time and find a deeper connection to something beyond ourselves. Maybe see a moose or muskox in their element.

The natural environment is our via negativa: gone is the noise of everyday life and the “normal” classroom. With each paddle stroke, we open up space for presence, silence, and a sense of the unknown—or even the infinite. Each stroke takes us further from routines and thought patterns, closer to the raw experience of nature.

Imagine now: you paddle once hard, and your canoe slides onto the sand of the riverbank, approaching a stark and beautiful area. We gear up and fish in the fog. We are remote. Everything feels like a mystery, especially the whereabouts of the Arctic char we covet.

You wake in your tent and have no idea if it’s 1 a.m. or time to get up for the day. The first few mornings are clear over the river, stretching up a valley of tan stone, gray rock, and thick green sedge grasses. Up on a ridge, a caribou looks down at us, nonplussed, then lumbers away.

Heroes:

This is the longest I’ve been away from my school, The Grauer School, where I have presided for 34 years. Over that time, the best teachers I have studied with have become my heroes. But education has hero issues. We need them as badly as football teams and pop musicians, but we don’t have many. A key sign of a declining civilization, it is said, is when its entertainers and athletes are the heroes. When I started my school in 1991, the number one reason people chose their schools in the U.S. was this: the football team. This is true.

Thich Nhat Hanh, a revered Zen Buddhist teacher who helped spread the practice of mindfulness and walking meditation in the West, passed away a couple of years ago. He was a hero to many and a master of silence. Shaun Martin, an American musician, teacher, and seven-time Grammy winner, contributed significantly to music education. Two heroic teachers—and they both focused on sound. Have you heard of them? We have trouble identifying our great educational heroes today—if we have any at all. Who is your hero?

My vision of great teachers always includes two components: how they interact in the classroom and who they are in the world. Who are they as human beings? What really makes us call them by this ancient, esteemed title: “teacher”? Where did they get their material: textbooks, life, or both? What forces have chiseled their souls into something we want to call Teacher?

I have wondered this wherever I’ve traveled, visiting schools all over the world, and I wonder about it routinely. It’s my field. So this is something I was thinking about even as we paddled north past vast reserves of the Canadian Shield, with rims of thin black spruce carving the way in long, forest-green lines, disguising the muskox and wolves listening to us.

We paddle. We think we are being quiet, moving gracefully, but to them, we are probably like a wrecking crew. I am paddling with some of the most accomplished technology experts in the world; it’s arguable that artificial intelligence might not be possible without some of them. Yet out here, we are an Arctic version of middle schoolers.

Indigenous Education:

Indigenous educational practices, passed down from the Inuit of this area, often integrate a deep connection with nature and periods of quiet observation and reflection as part of the learning process. Science confirms what they found obvious: just as birdsong calms our brainwaves, the sounds of nature—the earth speaking through the wind and the river, which I experience as silence—also calm the soul.

Maybe this is the unschooling we hear about. The via negativa. There are endless skills every school class and teacher can assign or allow their students. Your great teachers: did they assign states of mind, cultivate them, presume them, or ignore them? Did they deal only with content and not much with state of mind? I mean the great ones.

What about this as an assignment for our students? “Be immersed.” That’s it—that’s the assignment.

Making yourself engaged could be the top skill we and our students need, yet we rarely ask for it, often ignore it, or presume it. But of course, it can be taught. Our teacher heroes all managed to teach it.

Many kids I talk to see school as a never-ending series of assignments and grades. Asking them to engage themselves autonomously in a classroom is like covering their eyes and surrounding them with gnats—which will happen at the next campsite. They feel stuck, victimized. I know; I’ve tried it. Ask your class, “What do you want to do today?” Most will draw a blank and need guidance. How about this: “Now, class, your assignment is to experience silence.”

This approach is a premise in founding schools imbued with Socratic or Montessori principles, and it is spreading into hundreds of home and microschools around the world. Forest and traveling schools teach sensitivity to the environment as a basic skill.

Teachers: entertain the thought, even if it just means entering your classroom and asking students to simply observe—to be observers. Many will assume there is little to observe at school and no point in it. They have stopped hearing pure sound at school. It is mostly noise.

Try this assignment with students: Ask, “Why did you show up, and what do you need me for?” You’ll get superficial answers at first. But keep asking about each answer they give, maybe a full seven times, until you get to the truth.

What if the assignment were to “go find awe”—the feeling you get in the presence of something bigger than you, something mysterious? Which of your students could do that? The most important assignment you ever give might seem ridiculous or unbecoming of a student. So go there.

They can find that awe in stories or art, and they will find it in their heroic teachers.

We were moving north, immersed in what many Indigenous people call The Great Mystery—what some call God, nature, or, in this case, tundra: treeless plains, the geographical version of via negativa. We begin to observe what our students might have thought was unobservable: a profound quiet. Direct observation of nothing itself. The rhythm of the paddle is a form of concentration, a pursuit of nothing.

Impact of Noise Pollution on Academic Performance:

Research indicates that chronic exposure to high noise levels negatively affects students’ learning outcomes. Studies find that students exposed to higher levels of noise pollution have lower reading comprehension and memory retention compared to those in quieter environments. I don’t know what your school is like, but noise pollution is not rare; it is common, and it is usually ignored.

Weirdly, silence disturbs many of our students a whole lot more. You can find them slapping on headphones and streaming heavy metal music to get away from … the noise of silence.

Our carefully measured exercises, curriculum, and protocols rarely provide time to tap into the spirit of each child—to draw upon their unique observations as scientists and artists must—or to plumb them, not for their facts or memories, but for their innate wisdom, wherever thought and spirit live.

Part 2: The Challenges of the Environment

Paddling 5 hours a day, we begin learning the unpredictability of the arctic.

We start out with a few days of mixed sun and warmth, taking dives into the Horton River when the sun allows it, always moving north under the gaze of caribou on the bluffs. And then the Arctic asserts its dominance. One day the temperature ranges from 37 to 76 Fahrenheit, and then the rains come like a soft tapping, for a while in clotting mists to fuller sound, then letting up in a damp stillness. Brushing my teeth, I abandon the view to stop the ‘squites and gnats from charging into my eyes, and then my ears and up my nose.

Rain silences purely. It is elemental, survival-driven, and I have streamed its sound in many classrooms. Next day, we paddle in it. A heading wind comes, and each paddle stroke is strained in pushing against this. We think only of rhythm. The thud and glug and play of waves on the canoe hull, and the flush and drip of the paddle stroke can become a form of silence when they are so steady and rhythmic that you can forget them.

Eventually, you can even learn to paddle silently: after each stroke, slide the paddle out horizontally, then, in one smooth motion forward, slip it in straight down at a perfect 90-degree angle and then pull—creating no sound when done right. Paddling, something tells me that the original people on these waters used silence in ways we’ve long forgotten. Silence could have meant survival.

We are days without a sunset, surrounded by the boreal forests of black spruce and the tundra. Paddling on, one can experience something profound—the sound of silence. Travelling north is a decompression as interruptive noise dissipates more each day away from it. The silence here is not just the absence of noise but the presence of something deeper. The Arctic environment is mainly a sensory experience. The river becomes so quiet you don’t want to interrupt it.

And you notice you have begun talking in whispers. Over the first couple days, I had noticed my hand involuntarily reaching for a cellphone and, of course, realizing there was none out here. I understand virtually all my students and teachers experience these feeds constantly back home. And we realize that noise is not only sounds, clangs, and voices, but that we also hear random states of mind—mental noise we can leave behind (or that can drive us mad).

Back there, all day long at our school in Southern California, in various locations, on flat screens, we cycle photos and live feeds from natural environments, sometimes including their natural sounds of silence. Think: bears hunting salmon on a live feed from Alaska. If you, teaching class, show similar scenes in silence to your students for 20 minutes or so once per week or so, letting go of the map, your kids and you could gain more than any lesson plan you could craft. And you may learn more about them than you anticipated.

Part 3: Education and Indigenous Insights

Go forth. At the end of 6 or 12 years of schooling, what will we have equipped the graduate with? What skills? What mindsets could replace the numbers we use to represent what a student has been through? What perspectives? What lasting impressions?

People often ask whether interruptive technologies need to be controlled in a classroom. To this, I would say that’s not the real issue. When we find our educational heroes, we’re not usually seeking the information they can provide. What they offer us is something greater: the creation of an environment, an ecosystem of learning, and a way of being that profoundly shapes how we feel. This world they create is unique. It is nondisruptive. It connects to everything in our lives. It is integrative, and those connections are pathways to deeper understanding.

As for disruptive technologies, even scrolling through a cellphone with the volume off is still too loud. To survive and thrive in the unknowns we’re preparing our students for, they may need a quieter attunement—a sensitivity to the nondisruptive.

Back home, both interruption and noise pollution have a constant impact on education and cognitive function. Noise pollution interferes with sustained attention. Irregular and synthetic noise impairs cognitive functions such as problem-solving, decision-making, and short-term memory.1

Sure, some of us can concentrate on a subway. But beware of the teacher so skilled at focusing in chaos that they fail to recognize the environment they’ve created—a place where they can access personal silence while some students hear nothing but noise. It’s heartbreaking to enter a classroom where a well-intentioned, well-prepared teacher is so focused on group work and high involvement that you can see some students will never even conceive of peace of mind and deep concentration—no matter how busy they appear.

And we know exactly who those students are. They rarely manage to concentrate amidst this busyness. We rarely attribute it to noise, even though noise is often the cause. Sometimes, we call it ADD.

In the quiet waters of this part of the Arctic, where the surface reveals only hints of the life beneath, we find grayling and Arctic char moving gracefully in the white noise eddies of stream beds, carried naturally into their slow, slithering motions by the river’s soft flow. There, amidst shifting currents formed where stream beds join the river, some of our canoeists—though not me—seem to have a rare gift: the ability to present bait in a completely non-distracting way. The fish take it naturally, without hesitation, as if the line itself were part of the water’s rhythm—a seamless integration into the ecosystem, like one hand clapping. (My bait, by contrast, presents more like two hands clapping.)

It is the great teachers who instinctively create environments where knowledge emerges naturally, unobstructed by the subtle distractions unnoticed by others—cultivated spaces where learning unfolds effortlessly and without interference.

Part 4: Deep Listening and Understanding

The farthest north I have ever been was not in a titanic cruise ship or a hotel that protected me from the elements. It is in this thin, 80-pound, polyvinyl canoe, completely exposed to the elements, here in the Northwest Territory, gliding further north on this river. The latitude is north of Alaska, north of Norway. As you paddle north, you sometimes think the sun will burn through the haze that seems to hang over the arctic horizon, then… is suddenly covered with a shutter of rain and rush of wind.

After some days, between paddle strokes, you lose track of whether these shutters you hear are in the outside world or inside your mind. Is what you hear the natural world, or between your ears. Maybe it is all merged—all part of the same circuit, matrix, God, ecosystem, soul, and mystery.

The sound waves strike the eardrums. The tiny hairs vibrate inside the cochlea, convert to electrical signals going to the brain. However, the brain does not turn off during silence—it often becomes more attuned to other sensory inputs or internal thought processes, still sending signals. This heightened state of alertness or internal focus may contribute to distractions, making it harder for students to concentrate or retain information in a noisy environment without a paddle. Or it may make us simply more aware.

Students are not graded on the quality of their concentration, though. Teachers are not paid for the quality of student concentration. Why not? They are more normally paid to locate and reward those students who already can concentrate in all weather.

Silence, especially in a learning or reflective environment, allows the brain to transform outside auditory stimuli to into memory consolidation, reflection, and deeper understanding …. In fact, the absence of sound in the receptive mind, or paddler, may encourage more profound cognitive engagement, as the brain is now free to process those other sensory or emotional experiences.

In sum, silence can be as impactful as sound, and healthier—it creates space for mental clarity and deeper comprehension, especially in contrast to environments filled with constant noise.

The boreal region, a vast forested belt of the northern latitudes which few of us have ever given thought to, is the largest land ecosystem in North America. And the most remote. In our canoes, we see no human for hundreds of miles of river. Farther out on this territory, the mines, developers, loggers, and industrialists pose a constant threat to this land, all under watch. They have shipped their excavators, drills, bulldozers, haul trucks, crushers and conveyors—loud to even think about—up here last winter on ice bridges, like bones of ancient mastodons, where they laid in silent wait of summer. We paddle well north of them, each stroke a three-part rhythm.

Now it is summer and, not here but miles from the river, they are mining. They mine under the constant eye of the indigenous who love this land, who can still live in villages scattered around. These are the indigenous who first made contact with the white man as fur traders, at outposts, and who still to this day will gladly share their advice on how to approach a grizzly bear:

Silently. Peacefully.

Voice of the Land:

Some small village First Nations people live on land that was taken from them, another kind of silence, the silence of having no voice, and of old, back-room historical treaties, land dispossession, and colonial practices. Some read and hear nature in ways we have forgotten. They have sparked a movement, alongside a constellation of like-minded conservationists, elders, and scientists across Canada and the world. Indigenous communities are reclaiming their voices as stewards of the land, and the Indigenous knowledge they whisper, even the old languages—carried in the wind for hundreds of years—is being recognized and integrated with modern science. They are becoming teachers.

Collaborations between First Nations elders, conservationists, and scientists may be making possible a more holistic, ethical, and wise approach to environmental protection. History shows they tried this with the original settlers, and failed horrifically, lethally, but this time, it feels as though others are listening—hearing words they spoke 500 years ago, before their language and ways were stolen, for the first time.

In a parallel movement, acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton has co-founded Quiet Parks International (QPI), a nonprofit dedicated to putting natural quiet within reach of as much of the world’s population as possible by certifying and protecting peaceful places2. Is quiet a place after all?

Up here, a massive mosaic of rivers and lakes runs through lands rich with potential gold and diamonds, marked by violent disturbances. Studying and navigating them means understanding subtle or brash turbulences, currents, roots, rocks, eddy lines, and surges. It requires noticing the quiet things—the slow-motion sounds—far from the dirge of daily existence and the constant noise our students will learn to ignore, but to which part of their mind is submerged.

There’s a gentle mystery to paddling this long river north, as if its quiet currents hide a secret soul below. Paddling, you forward ahead inches at a time. First you are in awe, as an observer, but eventually you just fit into it, and you can hold a cup to your ear, like a bear’s ear, and the river is all the sound in the world, nothing more or less.

Spiritual Traditions and Modern Challenges:

We are told to “let it go” by all the major spiritual traditions, to paddle the via negativa, and yet we are also told we must be warriors and speak out. What about a philosophy to be quiet and to have a voice, both?

The greatest honor our students can pay us is trusting us enough to believe that they can be heard and that we can be quiet enough to listen—not just tell them if they are right or wrong. It’s about making them know they are heard—about exploring what it means to listen to our students. When we create an environment where they feel safe and valued, we are creating a different kind of connection and understanding—one where we stop listening for right and wrong and we listen for understanding, connection, or just the pure intrinsic value that lies beyond achievement. The psychological and emotional benefits of students feeling heard, coupled with the beauty of a teacher who truly listens, represent a gold standard of great teaching—an approach I often associate with the Socratic method.

The history of quiet or silence in education runs deep, from the philosophical traditions of Socrates and his focus on listening. In the monastic schools of medieval Europe, and still today, silence is considered essential for contemplation, prayer, and deeper learning. The Jesuits, credited with starting the university system, incorporated periods of silence for reflection and prayer in their educational practices. No high school teacher or graduate school of education ever mentioned this to me.

Of course, enforced silence can be a harsh control tactic, reminiscent of industrial revolution-era schools and the use of hickory sticks to ensure complete compliance. In response to such practices, new movements emerged as educators like Maria Montessori and John Dewey introduced progressive models that prioritized individual student needs, incorporating periods of quiet reflection and self-directed learning. Quaker schools, rooted in their belief in “inner light,” moments of silent worship, encourage reflection and introspection. Unlike enforced silence for control, this practice fosters inner growth and self-awareness. Today, there has been a growing recognition of the benefits of mindfulness and contemplative practices in education.

Many years ago, I kept noticing at the start of our weekly assemblies that one well-intentioned teacher or another would tire of all our students gabbing and shout, “Be quiet!” across the hall. I found that demand resonating between my ears even after the sound was gone, as if we had established a very loud form of silence. Spiritual feedback. Eventually I purchased a Tibetan singing bowl and began allowing it to sing, running the drumstick around the rim until it resonated with a sustained, harmonic tone, which also made me smile. The sound, that harmonic resonance which I equate with the silence of nature, that smile, encapsulated all the voices and gradually stilled everyone, all students rapt, and I wondered if that’s what silence was. Eventually, in assembly, and in canoeing, there is no specific moment when the silence begins, and pure silence can be like a dawning. It is quiet silence. Eventually, more students wanted to learn to make the bell sing like that themselves, discovering silence as a consciousness for the first time.

Mindfulness and Silence in Education:

Noise and its anxiety or irritability among students, is what we often call pollution. This not only affects their mental health but also their behavior in the classroom. A study by the Acoustical Society of America found that noise-induced stress can lead to increased aggression and a higher likelihood of disciplinary issues in schools3.

We can take the opposite approach. In my case, I was born with a particularly high sensitivity to noise, which initially seemed like a problem but has turned into a significant asset as a teacher: sensitivity to the classroom environment. As a developing teacher, I was driven to create classroom ecosystems that fostered listening and concentration. I knew that if I could hear even the faintest sounds, my students could too. Over time, I became attuned to distracting noises on behalf of my students, transforming what once felt like a weakness—my distractibility—into a teaching strength.

Every step in the Arctic tundra can inspire mindfulness or bring disturbance—or the two may merge. In those Arctic moments, the potential for learning and introspection is immense. Almost everything feels like a metaphor: each footfall is unique, landing on a tuft, a critter hole, or an uneven stone. No step can be taken for granted. In some places, the ground is a mattress of sphagnum moss, yielding to each step and inviting careful, deliberate movement. With each soft step, we develop a growing awareness of our presence, embodied in the quietest footfall creation offers.

Once, many years ago on campus, in a rookie move, I declared a campus-wide day of silence. To promote awareness, I guess. It lasted all of one to two minutes, if that, and I quickly knew that two minutes of all-campus silence would make a more realistic goal. Eventually this is where the singing bowl came in: two minutes of pure silence per week. I was initially self-conscious in standing up front with it every week at assembly, waiting for the rich, sustained, harmonic overtones to ask for silence rather than my voice, but over time, it became part of our campus culture. Once it was, it created what were among the most connected, peaceful moments of each week. Pure.

Part 5: Universal Lesson Plan for Any Subject

- Play a video of a rainstorm.

- Alternatively, if possible, experience a real rainstorm with students—provided it’s safe and permissible.

- Sit quietly. No speaking.

- Invite students to either create something of their choice or simply observe their thoughts for a set time. Start with 2 minutes, and gradually extend to 20 minutes if possible.

- After the experience, ask students to reflect: What happened?

Remember the two-minute rule. Be prepared for the first attempt to feel chaotic—that’s evidence of its importance. Encourage students to try again. Debrief after each session, repeating this process over several weeks. Each time, ask: What happened this time?

Over time, you may be able to take your class outdoors to find their own quiet spaces, restoring what could be the most basic form of education: simple sensitivity to the environment—something nearly lost in the modern classroom.

My friend went on a silent retreat in northern California for 10 days. I wonder how that would go in a high school.

Consider showing a nature feed on your flatscreen, if you have one. Let it run continuously, 24/7, like a window into a retreat that is going on—a quiet meadow or forest always within reach—where the sound is set just below or at a barely audible level.

Impact of Noise on School Environment:

Schools located in noisy areas, such as near highways or airports, face more challenges. These schools often report higher levels of absenteeism and lower overall academic performance. Efforts to soundproof classrooms and create quieter learning environments have shown positive effects, but those measures are often no more feasible or affordable than taking them paddling in the north country—the teacher is stuck with the classroom as is. However superficial this sounds, I love the white noise machines now on the market. Some Solfeggio frequencies, a set of specific tones believed to have healing properties, are also thought to resonate with universal vibrations, such as 432 Hz (claimed to be mathematically consistent with the universe’s harmony). We are discovering various other versions of silence. I like Brown noise. And I like a quiet river more, still. It’s all good, wherever you are. These frequencies can quiet a loud mind over time, especially if used habitually.

Part 6: Reflection and Learning

After three weeks in the Arctic, what I realized I had missed wasn’t something tangible—it was the relentless noise of hundreds of news articles and hours of streaming input. Catching up on all that back home amounted to barely 5 or 10 minutes of skimming. The wild serves as a powerful reminder of the constant information overload we endure and the value of silent, uninterrupted contemplation as a cornerstone of teaching and learning. Once home, I unsubscribed from every feed I had.

We and our students benefit greatly from reducing information overload and focusing on mindful listening and learning. You already know this, of course. The absence of constant digital input in the Arctic fosters a deeper connection to the present moment and a more profound understanding of the natural world. While we can’t always call on a bush pilot and a float plane, the via negativa of the Arctic is still available—between our ears.

Initially, our students and teachers may perceive this absence of overload as boring or a waste of time. Many teachers might fear it, feeling compelled to fill every minute with input, anxiously raised hands, and measurable activities. We grow uncomfortable or guilty, and our restless minds convince us that less input equates to boredom or unproductivity. “You were given a brain of incredible sensitivity, creativity, and energy, and you have no right to be bored. It is for you to engage your mind—no one else, no teacher, no technology,” I tell my students.

We can be fearless and committed, continuing to study this phenomenon, finding ways to embrace silence, to seek it out, and to sustain it—along with the infinite potential it holds.

Conclusion

The hush of a place is something you always remember and keep with you. On the river, the normal soft plop of the blade entering the water, the swish of the paddle dripping, can become silence. In this silence, I imagined I was indigenous, in a birchbark or moose skin canoe, or a fur trader—maybe hungry, or cold, maybe needing to approach prey. Or to approach a deeper understanding of my surroundings.

Silence & Lessons in Listening:

Background noise can make it difficult for all of us in our studies. Even moderate levels of ambient noise can disrupt attention and make it harder for students to engage. Research shows that not all ambient noise is equally disruptive to concentration, though. Irregular, random, or unpredictable sounds—like sudden conversations or sharp noises, or even noise from another student group—are more distracting because they require the brain to process unexpected stimuli. In contrast, steady, low-level noise, such as white noise or the hum of an air conditioner, is much easier for the brain to tune out. Human speech, whether in music or from a nearby student group, is particularly distracting, as the brain naturally tries to interpret it, making it harder to focus. And human speech, of course, is practically incessant.

Not all my students have accepted this fact—perhaps some were fighting their own addictions—but most have been willing to consider what is distracting them and recognize that not all sound is created equal, even at low volume.

At the end of our paddle, we portaged from the river over to a lake where the floatplane would attempt to pick us out of the fog the next day. That night, the first and only natural sound of the week that I might not call silence—the haunting, wacky, and most unstudious call of the loon—reached our eardrums. Human noise does not happen outside our vibrating eardrums, but inside them, inside your mind. This is where the peace is. I want that for you and your students.

Whether it’s in nature or the stillness of the classroom, silence can shape deep learning and growth.

Ask your partner, or a colleague, or a class a simple question if you are willing:

- When was the last time you experienced great listening?

- When was the last time you experienced this beautiful sensation in a classroom?

- What would it be like to create an experience like that?

- Can you listen your students into learning?

If we can take our students and teachers to the forest or river to listen to loons calling and falling silent, the floatplane—first experienced as a subconscious drone, then as a distinct hum signaling the end of stillness and the packing of our bags for home, where we might carry new thoughts on silence and the silent mind—I’m all for it. But, of course, I’m not suggesting you do that. What I am suggesting is:

- That great teachers might embrace silence rather than rush to fill it.

- That great teachers understand silence can include natural sounds that quiet the mind.

Absolute silence, in the literal sense, does not exist. Sound is the vibration of particles, and even in seemingly “silent” environments, vibrations are always present—sometimes known as Schumann resonances, frequencies around 7.83 Hz: the Earth’s “heartbeat.” Meanwhile, your own body hums, and perhaps your canoe paddle leaves a few perfect drips in rhythm. Ultimately, what we mean by silence is what we create in our minds, for ourselves and our students. Silence is the achievement of pure listening—perfect listening.

In Arctic silence, sensitivity to the environment deepens, and a stunning world can reveal itself more fully. With practice, we can bring this clarity and quietude home, sharing it with our students whenever we fully receive them, wherever we are.

If we, as teachers, parents, and colleagues, became perfect listeners, we would eventually hear from our students the most natural things in the world. We could be attuned to what they are hearing, as though we are hearing them for the first time, and receive it with nonjudgment and a genuine sense of curiosity, free of agendas—just as we wish for them. This is silence.

Reference List

Amundsen, A.H., Klæboe, R., & Aasvang, G.M. (2013). Long-term effects of noise reduction measures on noise annoyance and sleep disturbance: The Norwegian facade insulation study. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133(6), 3921. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4802824

Haines, M. M., Stansfeld, S. A., Brentnall, S., Head, J., Berry, B., Jiggins, M., & Hygge, S. (2001). The West London Schools Study: The effects of chronic aircraft noise exposure on child health. Psychological Medicine, 31(8), 1385-1396. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701004696

Klatte, M., Bergström, K., & Lachmann, T. (2013). Does noise affect learning? A short review on noise effects on cognitive performance in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00578

Quiet Parks International. (n.d.). Home. Quiet Parks International. Retrieved December 14, 2024, from https://www.quietparks.org/

Shield, B., & Dockrell, J. (2008). The effects of environmental and classroom noise on the academic attainments of primary school children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 73-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.11.002

Stansfeld, S. A., & Matheson, M. P. (2003). Noise pollution: Non-auditory effects on health. British Medical Bulletin, 68(1), 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldg033

Teresa of Ávila. (2008). The way of perfection (E. Allison Peers, Trans.). Dover Publications. (Original work published 1583)

World Health Organization. (2011). Burden of disease from environmental noise: Quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/136466/e94888.pdf

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Compendium on health and environment: Environmental noise. https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment/environmental-noise

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Stuart Grauer for Intrepid Ed News.