August 16, 2024

My family and I travel to Paris every other year to visit my mother. We spend a week there, then take the train to the West Midlands in England to visit Charlotte’s parents. These trips are a mix of the familiar and the new: while we stay in the same apartment and have slept in the same configuration for years, my children grow up, and our experiences are different every time, even if the location remains the same. As I look up from this screen, I see the bit of carpet where my son Nico took his first uncertain steps, and where, more than 17 years later, he and I watched the 2024 European Cup, having a drink together (legally). In the meantime, Nico’s sister Alexia was born, their mom and I divorced, and meeting Charlotte created a blended family. The trips to France are important markers in our lives, markers that include my mother’s own ritual of notching the corner of the doorway when she measures the children’s height on the first day we arrive. (My own grandmother used to do the same with my cousin and me.)

I do love Paris. It’s the place where I grew up, and it’s important for me to foster a connection between this place and my children, who carry French passports but have never lived in France. So we try to have different experiences, but some are our favorites. What better way to become intimate with a city than to walk its streets, to point in a direction and just go, without much of a plan? And so we walk and we talk and we stop for a bit of food along the way. It’s not a bad life, and for that I am grateful.

Paris materializes through the Seine River, where a small island once served as a defensive outpost for the Parisii, a small Gaulish tribe, in the 3rd century BCE. Paris materializes through the buildings made of stone—some of which date from Cardinal Richelieu’s 17th century urban planning projects—and Paris materializes through the cut woods that made houses that no longer stand, yet are integral to the city’s story. Paris materializes through the museums that host the paintings of artists like Edouard Manet, whose brushes were most likely made of hog bristles or sable hair held by copper from the earth and wood from a tree1.

Place is the materialization, the embodiment even, of the stories of its entangled participants—human and more-than-human. Paris is the aliveness of these stories. It materializes through life’s stories. So does every place.

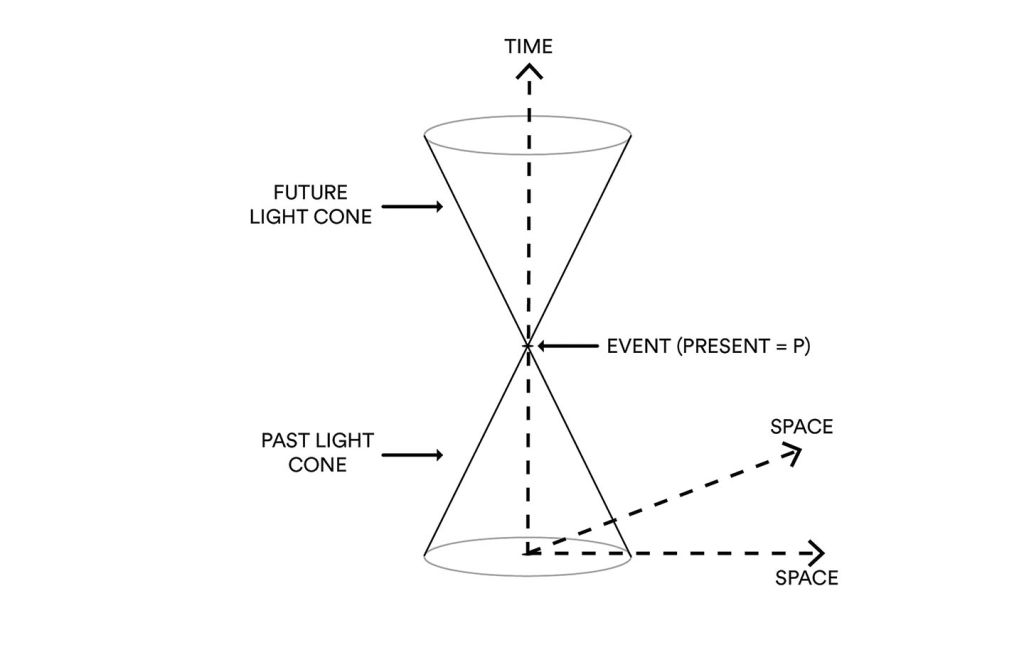

Place cannot be reduced to its geographical, economic, social, or cultural characteristics. Place is more than its topography, commerce, demographics, or art. Place does not exist separately from past and future, from the humans and more-than-humans who participated in its making, in its worlding. Place emerges from past events, the specific occurrences in spacetime, that have led to this moment, in this location. Place is the temporary culmination within a continuous process that began with the Earth 4.6 billion years ago—nay, with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago—a convergence of space and time, spacetime that was always one and the same. Place is the pottery made of clay that served before the Romans came. It is the pigeon that pecks at the crumbs of bread on the sidewalk. It is the people long dead who dug into the ground to evacuate the filth that flowed through the cobblestoned streets. Place is the materialization of the relational process that is life2.

Place is also the relational processes localized far away, in other places that have suffered from colonization, extraction, and subjugation. Place emerges here through what happened then, over there, eliminating any distinction between here and there, then and now, all entangled into many realities.

Place is relational, it is not an objective, disconnected entity, separate from our shared experiences. It is situational, it is not fixed. It is entangled, not delineated.

I write these words in my mother’s apartment, its walls made of limestone formed from the skeletal remains of marine organisms such as coral, foraminifera, mollusks, and algae. I sit at a wooden table—the tree’s origins unknown—which itself lies on a woolen rug—of a sheep unknown. I type on a keyboard made of fossil fuels—the carbon remnants of ancient plants and animals compressed over millions of years. Everywhere, life marks this experience.

Nature is not “outside.” Nature is everywhere. Nature is relational. We are Nature. And if this is so, then the word nature dissipates because there is no separation. We don’t “go out in nature.” Nature is not “out there,” it is not somewhere we visit, somewhere we enjoy. We do not Disney-fy nature.

We do not other nature.

In schools, it appears specious to take students outside, to dedicate time for them to reconnect with nature, to include special lessons on sustainability. While well-intentioned, these are often add-ons and rarely get any traction toward deep learning. We take learners out of the classroom and have an experience upon which we might reflect in the moment about how great it is to be outdoors. We then all return to the artificial lights of the building, sit at desks, and carry on delivering the same curriculum that reifies and sanctifies the cognitive over other ways of be(com)ing—feeling, sensing, intuiting, and communing. I am not discounting that these are important steps to take, but they are not the destination3.

Rather than treat nature as something we need to go out into, something outside, somewhere we go, we learn to understand that there is no fixed separation between indoors and outdoors, between civilization and wilderness, nature and not-nature. These permanent binaries fail to notice the infinite entangled participants—human and more-than-human—from which this place emerges (worlded as a relational process).

When we notice the participants, when we listen to their stories, we develop, in the words of biologist E. O. Wilson, the “urge to affiliate with other forms of life [which] is to some degree innate, [and] hence deserves to be called Biophilia.”

We are surrounded by the stories of life, in fact, we co-author these stories as we too are participants.

Look and listen around you. Where do you notice the stories of life? Where might they be uncovered? How might 3.8, 4.6, 13.8 billion years come together here in this moment, in this that emerges as place4? There is no “going out in nature.” The walls that we have erected to separate us from nature, physically and metaphorically, blur as they are (also physically and metaphorically) constructs. The walls are nature. They too are stories.

The shifts are subtle, perhaps imperceptibly so, yet ontologically meaningful. Rather than “take students outdoors,” we go to different learning spaces that may once have been designated as “outdoors.” We stop seeing our buildings as separating us from the natural world anymore than we would consider a rabbit’s burrow as separating him from nature.

In schools, this means no longer making permanent mental dissociations between indoors and outdoors. Life participates everywhere. We learn to notice stories.

Rather than approach nature as something to observe with objectivism, something we hold at a distance so that we might torture secrets out of her, to paraphrase Bacon, we appreciate that we are entangled [with/as] everything in the universe, as nature, as the world, inextricably connected [to/as] all phenomena, all events that mark spacetime. We emerge as matter from ripples within fields of energy that permeate all of space. This is not “woo woo”, this is quantum physics.

In schools, this means developing ecosystemic awareness alongside responsibility for how we approach the world as participants ourselves.-

Rather than operationalize our response to ecological breakdown, with techno-solutions or mechanical alterations to our everyday behaviors, we connect the inner with the outer work, rendering them indistinguishable. We cultivate the understanding that if nature is a process in which we are participants alongside everything in the universe, harm to the world and others is self-harm. To go further, we no longer commit acts of self-destruction and we no longer try to “act on the world.” We see ourselves as a unique expression of life.

In schools, this means going beyond recycling bins and compost heaps, the operationalization of sustainability. This means developing eco-literacies—the understanding of how life (self-)organizes—through our contributions to the thriving of all life. Learning experiences emerging from local (in spacetime) conditions with local responses. That doesn’t preclude drawing from global works of knowledge (otherwise known as disciplinary knowledge). On the contrary, we apply this knowledge to the uniqueness of this place in ways that contribute to thriving. We learn from infinite stories.

In Paris, while there may be only the faintest sounds of birds, while trees may grow in lines through the pavement, while sitting on the grass is often prohibited, life tells its stories everywhere. The limestone that replaced wooden houses, the pathogens that filled the air, the paintbrushes that helped create the paintings hanging on museum walls, and the inhospitality of the city for plants and non-human animals, this place is full of stories.

There is no going out in nature, there is no special program, there is no othering. Some places may be more conducive than others for certain ways of being to emerge (those fields again!), but there is no permanent binary, only perception, only approaches [to/as] the world.

Nature is no longer inaccessible when our perceptions change. We can participate in the emergence of conditions for all life to thrive. We world these worlds.

We co-author place and place co-authors us, indistinguishably.

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Benjamin Freud, Ph.D. for Intrepid Ed News.