March 4, 2025

Introduction: Why Executive Functioning Matters

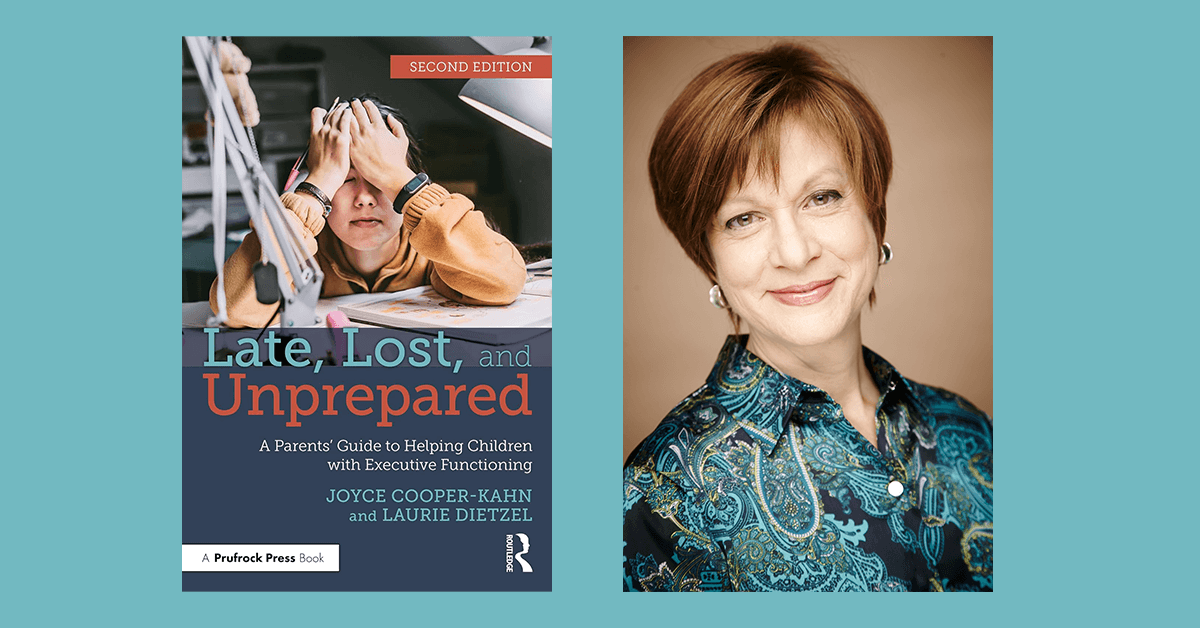

When I interviewed Joyce Cooper-Kahn about the new edition of her book, “Late, Lost, and Unprepared: A Parents’ Guide to Helping Children with Executive Functioning,” she modestly credited many of her insights as a child psychologist to what she’d learned from working with her clients. One example she offered was particularly moving.

Evaluating a 21-year-old college student who was struggling academically, Cooper-Kahn asked him if he’d ever heard of executive functioning skills.

He hadn’t.

She gave him an example of that mental checklist one reviews while packing the car for an errand or trip. “You know,” she said, “it’s that little voice you hear in your head.” Her client “fell totally silent,” Cooper-Kahn recalled. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard a voice like that,” he admitted.

Are some of University School of Milwaukee’s students missing that voice, too? What can we do to reset their frequencies so that it comes through, loud and clear?

Middle schoolers struggle with executive functioning skills involving organization and self-regulation, and there are legitimate reasons for this. Their young brains are still very much under construction. Middle school also represents a major transition in a student’s education. Students shift from having a single teacher in one classroom to having multiple teachers and classrooms. They must follow a block schedule, manage a locker, and complete more homework. This shift challenges even the brightest students. In fact, intelligence and executive functioning have little to do with one another.

But Cooper-Kahn is also playing the long game, and we should be, too. She recognizes that children are only in school for a couple of decades, and that they need to learn how to be independent as soon as possible. Yes: parents and teachers can help students develop good habits. But it’s ultimately the students themselves who must internalize habits to function well in the real world. And the time for middle schoolers to start doing so is now.

In the second half of Cooper-Kahn’s book, each chapter explores one skill related to executive functioning. Trouble with controlling impulses? See chapter 11. Problems with organization? That’s chapter 15. In these chapters and others, Cooper-Kahn teaches strategies that any parent can implement at home, ensuring that children can make immediate progress in addressing their deficits.

Building Toward the Future: Incorporating Executive Functioning

I asked Cooper-Kahn questions that I thought would be most valuable to middle school parents. This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

- Because executive functioning skills develop over time, how might a parent know if their child is at their grade-level developmentally or having more significant issues?

It’s really important to talk with the people who see a whole range of kids’ development. Most of us as parents see one or a few kids’ development up close. Go to someone like a teacher of a 5th grader or 6th grader and say, “How is my kid doing? Is he in the pack? Is anything standing out?” That is such valuable information. I think psychologists can be helpful, but school staff knows more about kids’ development than almost anybody else. They just have seen so many kids over the years that they help give us a yardstick for how our kids are doing. - What is the cause of executive-functioning challenges?

We know that the cause is brain based, and we know that it has to do with the way that parts of the brain are connecting and communicating with each other. Kids with developmental issues, like ADHD or autism spectrum disorders, may have executive-functioning challenges. But there are a lot of other reasons that kids can have trouble with executive functioning. A child may have developed all the skills they need, but something is impinging on their ability to use them, such as a mood disorder or temporary stress. - Why is assessment important?

We need to do problem identification. If a kid is disorganized, people may assume it has to do with executive functions. But then when we actually look more closely at what’s going on, we may identify the problem as being something else. For instance, a child who has language delays is going to have trouble following directions, so they may look disorganized. But in fact, the problem is they’re not processing the language demands well. So, we need to make sure we truly understand the child.

An assessment will also reveal a child’s strengths. That’s important because nobody builds a life around their weaknesses. We can use those strengths to help bring along some of the areas where they’re weaker. - Why are habits and routines so important for these kids?

Once something becomes a habit or a routine, it no longer lives in the parts of the brain responsible for executive functioning. If we can build in practice and repetition so that something becomes a habit, then kids can learn to do those things, and we can help them generalize across different tasks and different environments, and now they’ve really got something. So, you know, we may not cure the problem, but what we do is give them a way to recognize the situations where a strategy is needed and then apply it. - Why is it important to teach executive-functioning skills in context rather than through something like an evening class on organization?

We need to make sure that the child has an opportunity to practice strategies at the point of performance. For example, a teacher may prompt a student with something as basic as, “When you walk in the classroom, put your completed homework on my desk.” When the child does this a few times with this reminder, the teacher may limit her prompting by simply saying, “You just walked in the classroom. What are you supposed to think about when you walk in?” The child will call to mind, “Yes, I have to put my homework on your desk.” Eventually, the child will start to remember independently. Upon walking into the room, the child starts thinking, “When I walk in, homework goes on the teacher’s desk.” You cannot form a habit unless you repeat it in the situation in which it’s required. - You bring up a concept in your book called “fading,” which essentially refers to fading out support so that children can manage tasks independently. Can you describe what fading looks like?

Parents should offer support, but always with an eye toward developing the child’s independence. It’s important for parents to break down tasks into their discrete parts, so that their children can see exactly what’s required for accomplishing them.

For example, a parent might present a chore card to a child with a list of all the subtasks that go into cleaning their bedroom. At first, the parent could help with cleaning to show how each step is done. In time, the parent should expect the child to do each step independently and only check to see that the work is complete.

Finally, the parent should expect the child to do the task and check its completion independently. We call that “You be the parent.” For example, a parent might say, “I’m going to hand the checklist back to you. I want you to stand in the doorway of your bedroom and tell me whether, if you were the parent, you would say, everything is done. If not, fix it, and come back and hand me this chore card again.”

Instead of the parent remaining the first evaluator, the child becomes the first evaluator. The child does the task analysis. - Neuropsychological evaluations provide parents and teachers with a diagnosis and a list of special accommodations, yet there is no “fading” or off-ramp built into these documents. I worry that children who are 10 will still have these same accommodations in place in years to come. How can we make sure that kids are developing capacities to shore up their deficits and depend less on accommodations as time progresses?

If you’re not planning on “fading” out accommodations, you had better be really sure that that child is going to need them all their life. Of course, anybody in education or psychology has seen a handful of kids who have some limits on what they’re going to be able to do. But not most kids.

Most of the folks we see are just delayed, and if we work with them, they’ll be able to do what they need to do. For example, an anxious child may need short-term support in terms of extra time on tests, extra help from the teacher, and then, at the same time, they need long-term interventions for how to manage anxiety. Again, we don’t just want to leave a kid anxious, and assume they can’t do things. Nobody wants that for their kid. - You emphasize in your book that a parent’s calm temperament is essential for communicating with their children. Why is that?

We know from research that when parents are over-aroused themselves, like talking loudly or forcefully or when their blood-pressure goes up, their kids react the same way. On the other hand, if we can teach parents to have a calmer approach, kids’ behavior will follow. There is a physiological link. We all tend to get more aroused in threatening situations. Loud voices are threatening. Getting in kids’ faces is threatening. They will act as if they are under assault. Some kids will come out fighting. But the good news is that those same kids will have calmer interactions themselves when their parents learn to have calmer interactions. When you’re angry and combative, all that kids pick up on is your emotional tone. If you want to communicate information, you need to do it in a way they can understand.

Kids Aren’t Perfect. Their Parents Don’t Need to Be, Either

Cooper-Kahn told me that it makes her sad when parents say, “I am just the wrong parent for my child.” She replies to them without equivocation, “That’s not true. You are the perfect parent for your child; you’re just not perfect.”

None of us is. What Cooper-Kahn’s perspective can teach us is that judging ourselves or the children in our lives doesn’t do anyone any good. “Take the judgment out of it. Executive functioning issues are not a failing you have. This is a problem you need to solve. You need to know some tricks.” In the intervening 15 years between the first and second edition of her book, Cooper-Kahn stressed that a lot of educators and clinicians have developed new strategies that work. “Try out strategies that sound promising,” she advises.

And remember, this isn’t a knowledge problem. “What kid doesn’t know that they are supposed to be organized and track their assignments. They know that. But how do you do it? That’s the question.” Cooper-Kahn offers some answers. With teachers and parents in partnership, we can ensure that we prepare children for tomorrow, today.

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Elaine Griffin for Intrepid Ed News.