Taming To Do List Chaos by Systemizing the Work

April 30, 2024

I’ve yet to meet an administrator with extra time on their hands. I frequently meet administrators who describe having plates that are too full and who don’t see a way to improve the situation within their institutional context — a resigned stance that maintains status quo and burns the goodwill of the school employee. Do not resign yourself to churn and burn.

Your admin team is made of hard working people who come to work and have lots and lots of things to do. This article will show you a way to categorize and systematize that work in a shared mental model, so you can have a shared language for how you and the administrators get things done and how you conceptualize your work across departments and divisions. As knowledge workers, your administrators’ activities fall into four basic types described below. Some of this work adds value to your community, but some of it is wasteful. Some of it is invisible and slows you down.

All teams will make some amount of each of these types of work and no team is perfect, so the goal isn’t to have no wasted effort at all. Rather, the goal is to better see the wasted efforts and steadily reduce them over time.

To create a mental model for the mix of outputs from Admin teams, I”ve taken a page out of software design, a form of knowledge work, and adapted it to a school context. This will make it easier for school leaders to think in a new way about their activities, priorities, and efficiencies.

The Four Things All Teams Make

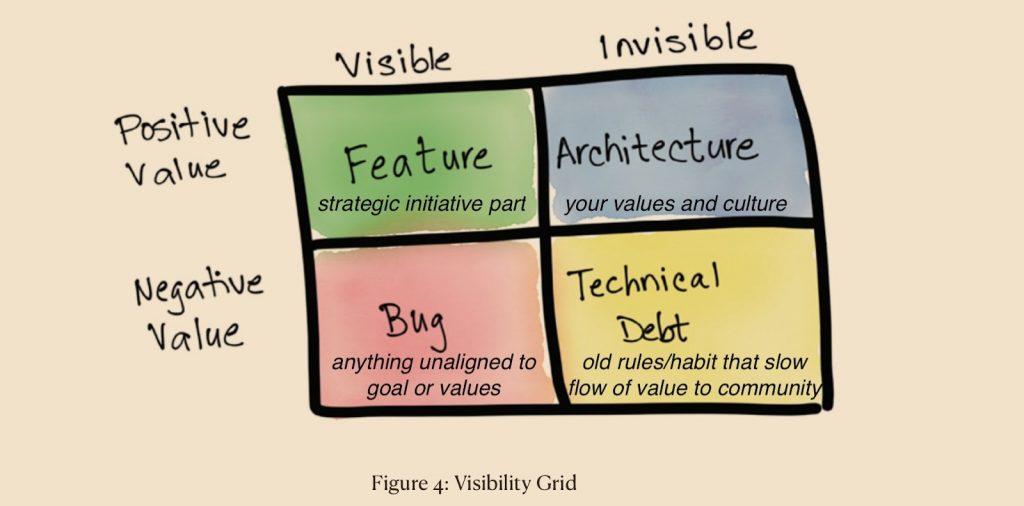

All teams make four types of things, seen below:

Source: Dominica DeGrandis, Making Work Visible, 2nd ed. 2022 [annotations added by Simon]

In this model there are two kinds of work: visible and invisible. Work has two types of overall value with respect to the goals of the school: positive and negative. While the value negative work is inevitable to some degree—the question is how much of it is getting made, and what is the proportion of negative to positive work getting done.

To delve a little deeper into the quadrants illustrated above, let’s look at the definition and some examples of each.

Your tuition payers are buying an experience and a set of outcomes for their child. Their child learns and grows due to programmatic features of your school. To improve the value of your school to your market you need to build or remove features from your program. A feature is a piece or part of a new strategic initiative or goal or initiative that adds value to the experience of attending your school or to your school’s business model. Examples of features include a new marketing campaign, a new course, a big ask of a donor, or a new business process.

Bugs are activities and actions not aligned with the feature being developed OR when features do not deliver intended value to intended beneficiary. Bugs will happen, but the goal is to make them more and more rare over time. In software a bug is something that prevents the program from running as designed. Bugs in a school are activities that are not delivering value or are degrading the value of your program to the students, their parents or your business model. Bugs take time, energy and resources away from reaching the goals of your school. Examples of bugs include a marketing campaign that flops, an adult negative culture that weakens people and their ability to work well, or a pet project that doesn’t relate to strategic goals.

Architecture, in this context, refers to the shared values and positive elements of your culture that help members get work done and guide action. Peter Drucker famously observed that, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” meaning that organizational culture is more powerful than a strategic plan or employee handbook. These are things that are felt but are not physically tangible. Examples of architecture include courage, integrity, an “all hands-on deck” mentality, a school’s value statements, leadership habits and practices.

And technical debt includes: the holdovers—processes, norms and rules from a past moment in time and a different market environment—that work against completing your strategic goals, sometimes heard as “just the way we do things here” without any rationale for continuing the practice or rule. This debt slows down growth just like a financial debt, dragging down people in getting their work done. Examples of technical debt include a weekly class schedule that few people love, autopilot spending, HR practices that are needlessly cumbersome or outdated job descriptions.

Drawing on DeGrandis’ excellent book Making Work Visible (2022), there are five forms of ‘time theft’ that organizational leaders participate in, knowingly or not. These thieves create bugs, hide technical debt, take energy away from building features, and prevent the hard working people in your school from doing their best.

The Five Thieves:

Too Much Work in Progress—work that has been started but is not completed. This is very common in schools—it looks like try to run too many initiatives at once and completing none.

Unknown Dependencies—something you weren’t aware of that needs to happen before you can finish a given piece of work. When an admin team isn’t well align and coordinated these dependencies slow down the work of completing features.

Unplanned Work—interruptions that prevent you from finishing something or from stopping at a better breaking point. This is common in organizations that make heroic ‘firefighting’ a badge of honor instead of a sign that a process failed to work in a sustainable way.

Conflicting Priorities—projects or tasks that compete with one another for focus, especially if there’s no clear priority. This is where leadership must be absolutely clear and communicate their top priority. There can’t be two top priorities, otherwise people become confused and focus is lost.

Neglected Work—partially completed work that sits idle (a natural consequence of the top four categories.) All schools have stalled ideas. The goal is to recognize what needs to be taken off the table and shelved so it doesn’t take away time or energy or resources from the strategic priority.

Improving your team’s ability to distinguish between the four fundamental types of inevitable work can improve your admin team’s ability to deliver features, make fewer bugs, address technical debt and create and strengthen your organizational architecture.

The good news is that there are simple, easily applied countermeasures for each of these time bandits, provided that you are ready for the opportunity of a troubleshooting conversation. The conversation that will bubble up as you apply any countermeasure will help you locate which of the countermeasures below will be useful to improving your workflow.

Too Much Work in Progress [WIP]—use WIP limits on your work board/work information radiator to limit cognitive load and maximize focus on work underway.

Unknown Dependencies—spend more time in Admin Team meetings to thoroughly understand who needs to work with whom and across what organizational silos to ensure that a given work item can move at full speed towards completion. A thorough discussion upfront of the purpose of a project and how it will help the school at large thrive is a key part of aligning the team around important work and creating positive urgency around work.

Unplanned Work—interruptions are just part of the job of being a school Administrator—the question is how many and for what reasons. Unplanned work can often be a result of work that wasn’t sufficiently discussed and didn’t have the dependencies surfaced early in the work process. Bugs in the chart above are a form of unplanned work.

Conflicting Priorities—leadership’s job is to clarify strategic priorities for the organization. By using a work board/work information radiator you can make clear your priorities by the queue of items on your work board.

Neglected Work—Neglected work happens less frequently as you and your team use work boards/information radiators. The work board forces you to think and talk more before starting new work, so you have lower odds of abandoning work midway through and losing the time that had been spent to get something partly done.

Moving into a world with fewer time bandits takes (ironically) time, effort, commitment, and a willingness to try new things. Millions of people have done this in intense jobs outside of education for decades. Try using the four-square schema above to see what sort of work you are doing and use information radiators to keep the time bandits at bay. See if you can work in this model with another colleague and practice together—you will likely be surprised at what you can accomplish and how much more time you can find in your week. Good luck!

You may also be interested in reading more articles written by Simon Holzapfel for Intrepid Ed News.