May 26, 2021

I was worn out. Period after period, in the library with my sixth-grade Humanities classes, the effort to keep students on task and productive while researching was becoming futile. Students used to be able to focus on their work and remain engaged with their assigned topics about the Renaissance. What was different? Why did these sixth graders seem so unmotivated? It was the spring of 2014, and I was having difficulty reconciling the significance of the assignment with my students’ interest level and focus. Students had been allowed to choose their topics (from a list of 30); why were they so off task? I was not alone. A 2013 Gallup Poll starkly demonstrated a sharp and steady drop-off in engagement for students. I began to wonder how I might tap into more intrinsic interest and motivation with my students.

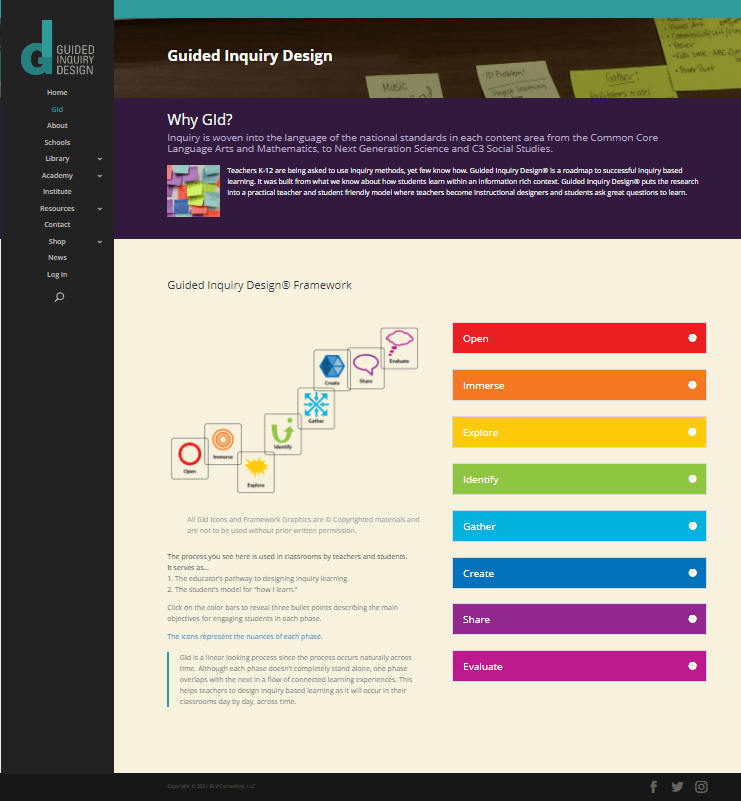

In the fall of 2014, our librarian shared an article with me that completely transformed the way I structure my classroom. In the ensuing years, my colleagues and I…