By

Bob Shaw Ed.D.

JK-12 Science Department Chair

Mary Institute and Saint Louis Country Day School (MO)

Scott Osborne Ed.D.

Fifth Grade Teacher

Meramec Elementary, Clayton School District (MO)

Each school year, many students return to school, knowing less about the content they learned than when dismissed for summer break. Student achievement scores decline an average of one month due to the decline during the summer. Circumstances will change this summer.

Summer learning loss (SLL), also termed summer learning effect, summer setback, summer brain drain, and more commonly termed, summer-slide, all describe the decline or stalling of academic achievement between school years, typically between the spring and fall terms in the American school systems.

To fully understand the problem, one must first understand that breaking up the school year to take summers out of school was not an agrarian model (von Hippel, 2019). In the early 1900’s New York City School administrators agreed upon a common calendar for schooling, reducing the attendance days from 248 to around 200. This plan allowed students to escape the non-air conditioned classrooms and travel with their families to the cooler countryside while the teachers prepared lessons and continued professional development. Sarah Pitcock of the National Summer Learning Association identifies “after more than 100 years of research on the academic setbacks related to students [varying lengths of summer break], and newer research on the employment and health implications of this disparity, it is clear that the summer slide is everyone’s problem” (Pitcock, 2015). David Von Drehle, in a 2010 article in Time Magazine, points to the barriers of economic cost and culture of tradition. “Adding days and weeks to the academic calendar are costly, and families want their children to have the carefree summers they had.” Schools are seeking a way to add academic time with minimal cost while allowing student mobility to visit grandparents, travel with families, or even have extended trips and camps. It is a strong preference to costly summer school or extending the current school year.

Many schools review materials covered in the previous year for the first two months of school (Dunbar, 2018). This reteaching period immediately reduces the learning potential by 20% every school year. As a result, by the time students reach sixth grade, they have spent almost a full year reviewing material taught earlier in their academic life. This review can hold strong students back while others catch up. Dunbar states that some struggling students may take five months to catch up, reducing their learning potential by 50%. Summer interventions have the potential to mitigate not only SLL but also reduce persistent achievement gaps (Kim & Quinn, 2013). Even worse, the SLL gap is cumulative. Donohue and Miller’s study went as far as to say:

“as much as two-thirds of the differences among students in rates of participation in academic tracks in high school, dropping out of school, and completion of four years of college could be traced back to summer learning loss that occurred during elementary school.” (2008, p. 19)

Entwisle’s faucet theory describes the school year as a period where learning is occurring because the “faucet” is running and summer as a period where learning is not occurring because the “faucet” is turned off (Entwisle et al., 2014). Interventions are needed to keep the “faucet” running for students during that summer period through an interactive web of real-world lessons intentionally targeting knowledge and skills learned the previous year. Also, Lave’s Situated Learning Theory connects the idea that learning is not prescribed but is a natural outcome of challenging experiences and embedded within an activity or context (Lave, 2016). Programs that focus on novel scenarios and exploration through problem-based learning can provide students with summer experiences with an academic purpose without the overprescribed feeling of the school.

The use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and home computers continues to grow among students in this age group. In 2018, the National Center for Educational Statistics (2019) reported that 89.9% of Missouri households have a computer or smartphone, and 83.9% of households are connected to the internet. This data shows an increase of 1.5% of homes with a computer or smartphone and a 4% increase in households connected to the internet in one year. Students are already spending more time on electronic devices during summer break, so guiding screen time is essential (Kraft & Monti-Nussbaum, 2017).

Our study replaced the ‘summer math packet’ with optional weekly online math and science review lessons to rising sixth-graders in two midwestern schools over the 10-week summer break in 2019. Students received both automated feedback from the online environment and teacher feedback in response to student questions or provided information students needed to acquire mastery. Students also had the opportunity to revise and edit their work. The online learning platform, Formative, allowed multi-media lesson delivery, individualized real-time feedback, tracking tools, which summer reading and packets did provide, and all students needed was access to a smartphone, tablet, or computer throughout the summer.

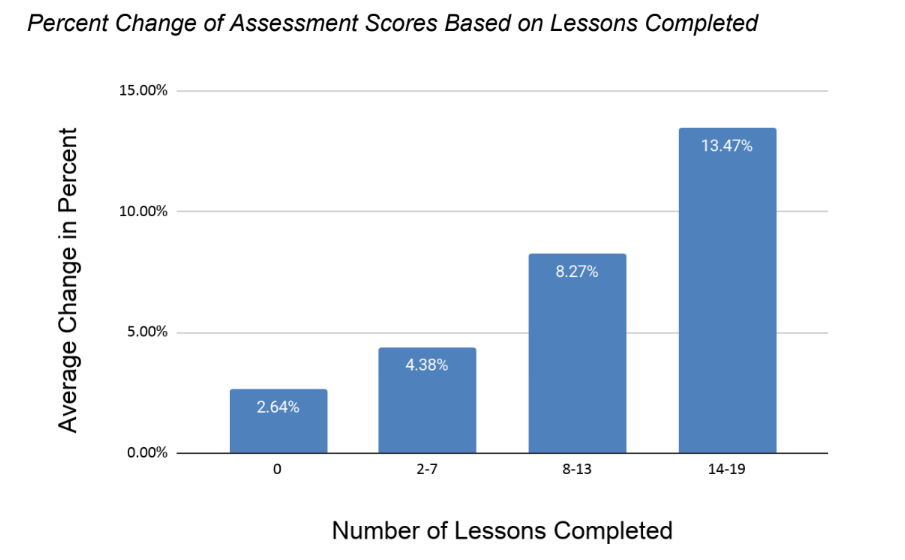

A test group, summer computer-based intervention group (SCBI), and a control group, completed a spring semester pre-assessment and a fall semester post-assessment to measure the change in math and science knowledge over the summer. Scores on an identical pre- and post-assessment were compared to measure the retention of skills from the fifth-grade spring semester to the beginning of the sixth-grade fall semester. The successful performance of the SCBI group on the post-assessment was statistically significant when compared to the control group. The data suggests that the more lessons students completed in the summer, the higher their achievement in the fall (Figure 5). With the onset of the remote learning environment, perhaps a systematic approach reviewing academic topics can give our students a way to make lemonade this summer while social distancing.

More information regarding this study is available upon request.

Scott Osborne Ed.D.

Fifth Grade Teacher

Meramec Elementary, Clayton School District (MO)

Bob Shaw Ed.D.

JK-12 Science Department Chair

Mary Institute and Saint Louis Country Day School (MO)

This article was written by Bob Shaw and Scott Osborne

Bob Shaw is a veteran science educator whose passion is to engage youth and adults in science and outdoor education. Shaw serves as Chair of the Pre-K through grade 12 Science Department at Mary Institute Country Day School (MICDS). His mantra of Seek, Discover, Share and Reflect has turned students into agents of science in their daily lives. Bob continues to teach two sections of science at MICDS.

Scott Osborne is a veteran fifth grade teacher at Meramec Elementary School in Clayton, MO. Scott is an innovative educator that guides curriculum and summer school programs, and specializes in math education.

Bob and Scott recently completed a joint doctoral research dissertation: Using Online Interventions to Address Summer Learning Loss in Rising Sixth Graders as part of a STEM Education Enhancement program in May 2020. They have set up Summer Computer Based Intervention programs focused on Math and Science at several schools and written several articles based on this research.